John Pavich and His Fifteen Minutes of Bolo Ball Fame

John Pavich (b. 1950) talks about his childhood games, his first jobs, and the memory of an epic Bolo ball record that made him a school VIP.

TEXT VERSION

Bruce Macdonald: I’m standing at the corner of Kitchener and Templeton; this is the twenty-one hundred block of Kitchener. And on the corner here is where John Pavich grew up.

John Pavich: I used to climb a larger tree than that— a chestnut tree— but they took it down years ago, when trees weren’t allowed to grow.

B.M.: So your memories are from the 1950s?

John Pavich: Late ’50s to early ’60s, from 1950 to 1969.

B.M.: Living across the street from Lord Nelson School, right here where the playground is.

John Pavich: There used to be a grocery store here and you could get ice cream, two scoops for a nickel and four for a dime. And the Cucciones used to live right here— Michael Cuccione and Mimmo Cuccione—he had a son who became quite famous because he was on Baywatch for a couple of shows and did a record with the Backstreet Boys. He died of cancer. David Hasselhoff came and talked at his funeral.

But, yeah, so there was a big thing about ping-pong bats back in those days. It was basically a bat like this and it was only like 5 inches by 11 inches wide.

B.M.: Bolo bat?

John Pavich: Bolo bat, or you could call them, there was another name for them… anyway, they called them Bolo bats, and the grocery store even sold them. And all these kids were told by this one guy who was probably in his mid-to-late teens that they were having a contest and you could win these badges and all that. If you hit the ball up in the air 25 times you got a little badge, which didn’t seem like a big deal, but the next week, if you hit it 50 times—and I think it went up to about 100—and you got this badge. He said “Well, in a couple of weeks’ time—or three weeks’ time you’re gonna win the Golden Bolo Bat.” I said: “That sounds more exciting. I wanna win that.”

So, I was only 10 or 11 years old then, and I remember I had Miss Mead as my school teacher; she was a Music teacher, and nobody liked her, but she was pretty good at teaching music. So I practiced with this Bolo bat. We used to have a couple of attic bedrooms upstairs, and my mother would say “go upstairs and play with that thing.” I’d walk to school all the way down here batting this thing— night and day I batted this ping-pong ball, on a three-foot elastic with a rubber ball at the end— night and day I became one with the Bolo bat. Then came the day for the contest. It was kinda chilly, and I wore this coat—it was quite a thick coat, I didn’t want get too cold. So, I positioned myself in the middle of a block down here… I have to go down there and see exactly where I was. There were a couple hundred kids. I figure it was from this right here to the end of the block.

Image credit: Donn B. A. Williams, public domain

B.M.: The whole block was full of kids? Wow.

John Pavich: So I figured, I wanna get to the middle of that block, because I wanna see people on my right and my left. You know, when you’re younger, everything looks a lot bigger. There were a lot of kids from all the way down that block.

B.M.: A city block is quite a mob. A city-block long…

John Pavich: And I had this big thick coat on, and I could see the (ball) strings drop, and every time somebody’s ball would drop, a group formed around them. So pretty soon it became me, and there was one group down there and one group there, and then those two elastics fell, and I was the only one left. So I kept hitting that ball, and the fellow who ran this contest was waiting for me to drop too and I wasn’t gonna drop it, but I was getting hot so I took my jacket off and I switched hands, so the kids were like: “He’s switching hands!” They couldn’t believe it. I was like a master kung-fu artist…. I’d just dreamt about winning this crazy Bolo bat.

So the guy says “Ok, you can stop now,” and I say “No, I gotta keep going,” and he says “No, you’ve won!, and I say “I have, I know, but aren’t I supposed to get…”. “Well, how many times have you hit it?” “I think about 5,000.” He said, “No, that’s impossible, it’s only been going for about 15 minutes, and if you got two hits per second that’s about 1,800 hits.” And I guess I was so excited in the moment that I forgot what I was counting. So, he said “I tell you what. The last week it was 1,520 or something, so we’ll make it 1,586 hits.” So that’s what he did, he put 1,586 hits.

I still have the bat after all these years; the elastic eroded many times. Basically, it’s just like a regular Bolo bat, but they painted it gold. Then they said “You can come down in a couple of weeks at the Orpheum or the Capital downtown and you can win a 10-speed bike.” And I was like “That would be a big deal,” but nobody wanted to take me down there. My brother didn’t want to take me down there. But, anyway, I was happy just to get the bat, so I was like a big celebrity at school for a few weeks. Even the Music teacher said “that’s pretty impressive”. So, that was my little day…

Image credit: Jack Lindsay, public domain

B.M.: Must have been the first time in your life when you actually really excelled at something. So did you move on to hula hoops later on?

John Pavich: Oh, we had hula hoops, yeah. Everybody had a hula hoop; they were a big deal. There used to be kids that used to climb this building here.

B.M.: Like rock climbing?

John Pavich: I couldn’t believe it. These two kids would climb it and get their feet on—this wall was painted many times. At the time, they used to wedge themselves on those spaces and climb up to the roof. I climbed the roof one time.

B.M.: Up to the roof? Holy Mole!

John Pavich: I climbed the back roof. There was a flagpole in the middle of the yard; it’s still there. I had that flagpole going back and forth about five or six feet on either side. You can still see it.

B.M.: You climbed the flagpole? Are you shinnying me?

John Pavich: I climbed the flagpole. I climbed that. I used to be the big tree climber in the neighbourhood. One big kid finally beat me, but I used to be one of the fastest tree climbers.

And I climbed the back of this school here on the drain pipe, and you know the roof is slated and, if you get on that, it’s really slippery. We used to climb these roofs like nothing. Like a bunch of monkeys.

B.M.: Did you have a Davy Crockett…

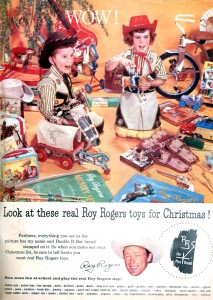

John Pavich: Oh, we used to have Davy Crockett hats, we had Zorro—that was the first graffiti, I think. We had a chalk on the end of the Zorro thing, and you put a Z, and it was pretty funny because every kid wanted to be Zorro. It was like a cape and a mask and all that stuff, yeah, it was pretty funny. Roy Rogers… I had a tricycle and I named it after Roy Rogers horse, Trigger,whatever. I’m not sure.

B.M.: Well, Trigger was Roy Rogers’s horse, so you must have named your tricycle after the horse. And what kind of things would you buy from the corner store across from your house?

Image credit: Megan Raley, CC, Flickr

Image credit: Tom Simpson, CC, Flickr

John Pavich: Ice cream! It was two scoops for a nickel and four scoops for a dime, and you’d get this double-scoop ice cream holder. I don’t think they even have those anymore. And grab bags, they were two cents…

B.M.: Two cents?!

John Pavich: Two cents to get a bunch of candies. Of course, my friend’s grandfather used to get that for a penny when he was a kid, or anything we got for a nickel he got for a penny. Everything goes up in price. That was a great little store, a loaf of bread was like 14 cents, half a pound of butter was like 30-35 cents. My mother used to run a tab there sometimes and pay the guy at the end of the month or week.

Image credit: Jack Lindsay, public domain

B.M.: Were there many immigrant kids back then?

John Pavich: It didn’t seem like there were so many, but I guess there were. You really didn’t think about that, you’d just play with kids, but there were a lot of mostly English and Scottish kids around here, then Italians started moving in. As I said, the Cucciones owned that big house. And there were some Japanese, some Chinese— it was quite a mix, actually.

We had a Mr. Harrison right across the street; he was a TV repair man. A Mr. Allen—he was an artist, a really awesome artist. And there was a guy who lived over here, an electrician. He worked for BC Hydro.

B.M.: I’m just remembering that in the ’50s a lot of the jobs were in the resource industry. There was logging and sawmills in False Creek; there was fishing, and agriculture. They were all big at the time.

John Pavich: My dad was a fisherman and soon after we bought the house here (my mom and dad bought the house for $4500 in 1950), in the summer of ’52, my dad and six other men went out on the Daisy Bee and they never came back. I would’ve only been one-and-a-half years old. So my mother was a widow at about 28 years old, with the three of us— my brother, my sister and me. But, you know, we always had something to eat. It was nothing fancy like today, with computers and wi-fi and YouTube and all that stuff. We played outside a lot: kick the can, all those games outside, like hide-and-seek. We used the whole block for hide-and-seek; it’s unbelievable.

Image credit: Dunbar History Project, public domain

B.M.: Did you ever find anybody?

John Pavich: I stepped on a bees’ nest once in a garage and, man, that was the end of that game for me! First time I ever got stung, about six times in my right leg. I stepped on a board to get up in the attic of the garage because my friend was up there. He said “Yeah, just step on those boards,” and all of a sudden I stepped on a bees’ nest! I beat him running that day, and he was one of the fastest kids on the block. He said “You beat me running,” and I said “Yeah, but you didn’t step on a bees’ nest!” I think they should use bees in every Olympic running to get the adrenaline going, man. That was funny.

B.M.: So what was your first job as a teenager?

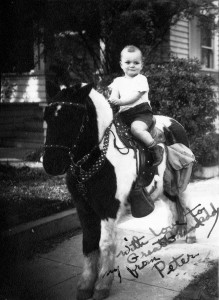

John Pavich: First job? Well the guys used to come around here and asked us if we wanted to sell berries door to door, and we would get like 5-10 cents per basket. We would go around the whole neighbourhood with a tray and ask “Do you wanna to buy some raspberries or blueberries?” They would buy them off of us and we’d make a few dollars. It wasn’t bad. There was a guy who would come around with a horse and get picture of us on his little pony, this arthritic little pony, and he’d come and ask the parents “Do you wanna buy this picture?” My mom had pictures of us every year on the pony— they went from black-and-white to colour, with the hat on and the holster…

B.M.: Roy Rogers days, I guess.

Image credit: Peter Taylor, public domain

John Pavich: And the other job I had was for a neighbour of ours who worked in the metal yard. He would give us radiators to take apart. It was aluminum, so we would take screwdrivers and spend hours taking a radiator apart to make like five dollars.

B.M.: Back in the ’50s people used to go picking things all the time Did you ever do that?

John Pavich: Picking things like berries and all that? I picked beans when I was about 12 years old. My aunt lived next door to Mr. Sitter who was one of the biggest leasers of land in Richmond to grow beans and mostly low-rise beans.

B.M.: Those are pretty hard to pick. You have to bend over, and it’s hot…

John Pavich: The Chinese people were the best at picking them. There was this girl who would pick a 5-gallon bucket, and she’d do two rows while I was doing one, while she’s talking to me, and she’d have this thing for them. The owner would come around saying “That’s a lot of yellow beans!” She would make $20 a day. I was lucky to make $10 and some of the families there wouldn’t make $20 between the four or five of them. Some of the old grandmothers would be there and they didn’t pick much, they just came out there to do something. But it was really hot.

My aunt—I was living at her house all summer—she was a great cook, so she would cook up all this breakfast for me, then I would have a big lunch, and she left me beautiful sandwiches, Boston cream pies and all this stuff. So, one day I was told by her that Mr. Sitter wanted me to do something for him that day. And he said “How many beans did you pick this morning?” “I don’t know, like $7?” And he said “Ok, I would give you $7 or $10, and I want you to come with me.” He wanted me to guard all these beans somewhere on No.3 Rd. And there was a whole pile of bean bags, probably several hundreds of these bags, big sacks full of beans. He didn’t want anybody stealing them, so I sat there guarding them. I piled them all up like a World War II bunker and laid there with my straw hat on; I could see right over the rise of these beans. And then, I must have fallen asleep, and I hear a truck, so I think “Oh, he must be here.” A guy gets out of the truck and looks around, then starts kicking a few of these bags. I said “Can I help you with something?” He said “Oh no, no, I’m just looking for…” I said “No, no, these aren’t those beans, get outta here.” So he took off.

B.M.: You were 12 years old?

John Pavich: I was probably around 12 then, yeah. I made enough money to buy some clothes and I remember buying this one jacket from Murray-Goldman. They had this ad that said “There’s not a single suit for sale at Murray-Goldman”, and he’d always give you two for the price of one. He had these advertisements where he was flying in the air; he was crazy. Anyway, at Murray-Goldman I bought this jacket, I wore it about twice and thought “Man, I spent $65 on this jacket!” I had made only about $150 for the whole summer, and I only wore the jacket twice and I hated it. I gave it to a friend of mine brother’s years later, and he just loved it. I thought “Thank God somebody got use out of this.”

B.M.: What was wrong with it?

John Pavich: I just didn’t like it. It was kind of… girly looking … As Arnold would say, “girly man.”

B.M.: So a good salesman talked you into it?

John Pavich: I don’t think anybody talked me into it. I just thought it was a cool winter jacket at the time, then I got some kind of weird looks when I wore it at school and I thought “I’m not wearing the stupid jacket anymore.”

Back in ‘69 I went out fishing on the West Coast to see what it was like to do seining, and that’s a tough job. I almost got killed twice out there. A guy let the skiff out in the middle of the morning, it was still black out, and I’m not even in the skiff (I was supposed to be the second skiff man). So yeah, fishing is not a fun thing.

B.M.: So there’s a memorial at Steveston?

John Pavich: Yeah, there’s a big needle, 8-10 ft high, and it’s for all those fisherman who passed away. It’s out at Steveston, there, at the park.

B.M.: How many names on there?

John Pavich: There’s seven names. My dad, Tony Pavich, on the Daisy Bee; Silvo Carr was the owner of the boat… My dad had an offer to go on another boat, but he said he’d already promised this other guy, Silvo Carr. So all these women were widows, seven widows…

Image credit: Sue B, public domain

Image credit: Sue B, CC, Flickr

B.M.: Back in the day, when there was anything except tourism, a lot of people got killed on the job, and there were lots of widows around. And now, with computers— everybody’s got a computer— less so I suppose today.

John Pavich: Well, my dad did also forestry work, and he was into coal mining in Cumberland, and he almost got killed coal mining. He got pinned against a boxcar, and the guy said “Good thing he’s got good bone structure, because he might have been crushed if he was a smaller guy.”

B.M.: Cumberland only went for six or seven decades, and 300 people died mining in Cumberland altogether. All those resource industries were very dangerous.

John Pavich: I remember, as a kid, that my mother was saying “Well, that’s the last time the milk is gonna be delivered by a horse.” I’m like, “Why?” She said “Next week, it’s gonna be a truck.” And it was right there in front of the house, at Templeton. He would stop this horse, get out and run up to the door to put the milk on the stairs, and then get on the horse. As a kid, I thought it was kinda nice, the horse. There used to be a junk man who used to go up and down the alleys, and he had a horse. Years after that, you’d hear the whip. Some of the kids, if they got near him, he’d crack the whip.

We had a sawdust furnace, and, if we wanted to have a bath, we had to chop some kindling and put it in this little potbellied stove which had little copper pipes inside that heated up the water tank.

Image credit: Dunbar History Project, public domain

B.M.: So you had a wood-fired hot water heater that you had to put wood in. And that was down the basement?

John Pavich: Yeah, there was a metal tank and the sawdust and the hopper. I remember one time putting the sawdust in there, and the chair fell off from under me, so I grabbed the hopper, and it broke off. My brother was trying to find me under all the sawdust. I ate a few pieces of wood; it was crazy. I thought I was gonna be dead. And then my mother was mad because we had to get someone to bolt the thing back on. Sometimes, if the sawdust was wet, it would stop, and we had to start the fire up again. We had a garage full of sawdust, and a basement with a room where you had to tar paper the wall, otherwise the sawdust ate away the wood. After that, we went to coal and wood, which burned a lot longer. Then one day my mom said, “I’m gonna get a gas furnace”—that was in the mid-to-late ’60s.

Leave a Reply