Bill Lightbown: “I Always Worked Against the Laws and Rules and Regulations”

Bill Lighbown (b. 1927) shares compelling memories of standing up for his Aboriginal rights, going to jail and meeting the love of his life.

– interview by Erin Grant

Childhood, Family, and World War II

I first moved to Vancouver in 1942; prior to that, I lived in Revelstoke. By the time the Second World War broke out, my two older brothers had already joined the airforce. My father worked away from home quite a bit of the time. He was an electrician—a signal maintainer, responsible for a big stretch of CPR. So it was my younger brother, myself and my mother that lived there. I thought I was a financial burden on both my father and my mother and I decided I was old enough to work. Once the War started, a lot of people who would normally be looking for work had joined the Army, the Air Rorce, or the Navy, so that meant that there were more jobs available for people who wanted to work, especially for women and youth. I decided to come to Vancouver, where there were more jobs available. My father worked for the CPR throughout the Depression and I remember the section hands—the ones who looked after the rail bed and made sure everything was working properly—raised families on their 10-cent hourly wage.

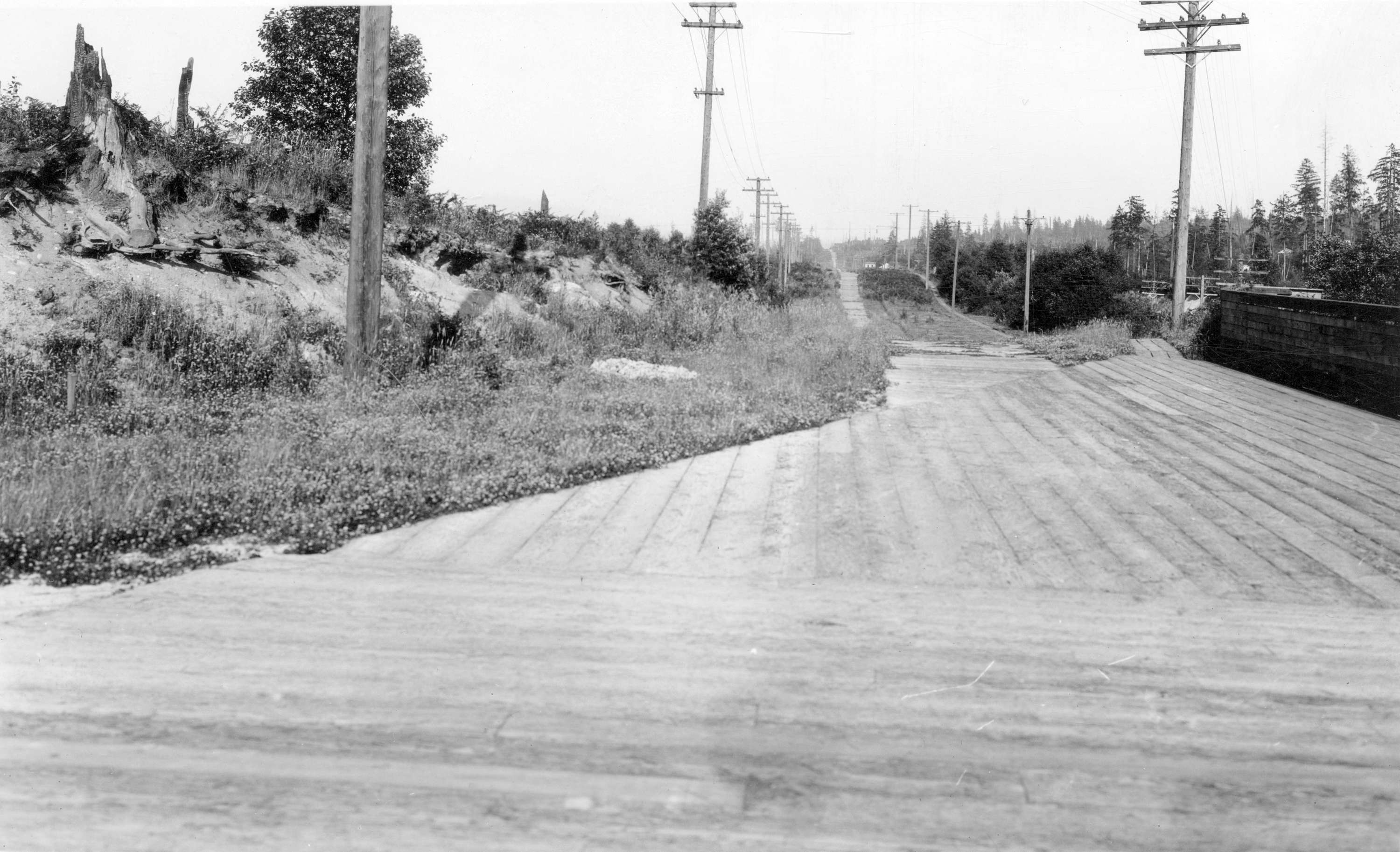

Image credit: Price family, public domain

Everybody was conscientiously supportive of the War. We didn’t know anything about propaganda but it was very effective. Canadians thought we had to fight the awful Germans and the Japanese. Both my brothers were bomber pilots, and my sister worked for Boeing on Sea Island. I was the second youngest. We had a half German Shepherd and half wolf family dog that we got from Indians in Alberta as a pup. He used to follow me to school in the morning at the west end of the Canot Tunnel—a 5 mile tunnel on the CPR line. It was about a mile-and-a-quarter to school. After we got to the school, he went home and was there when I returned. That dog must have had a clock of his own, because he was always sitting there waiting.

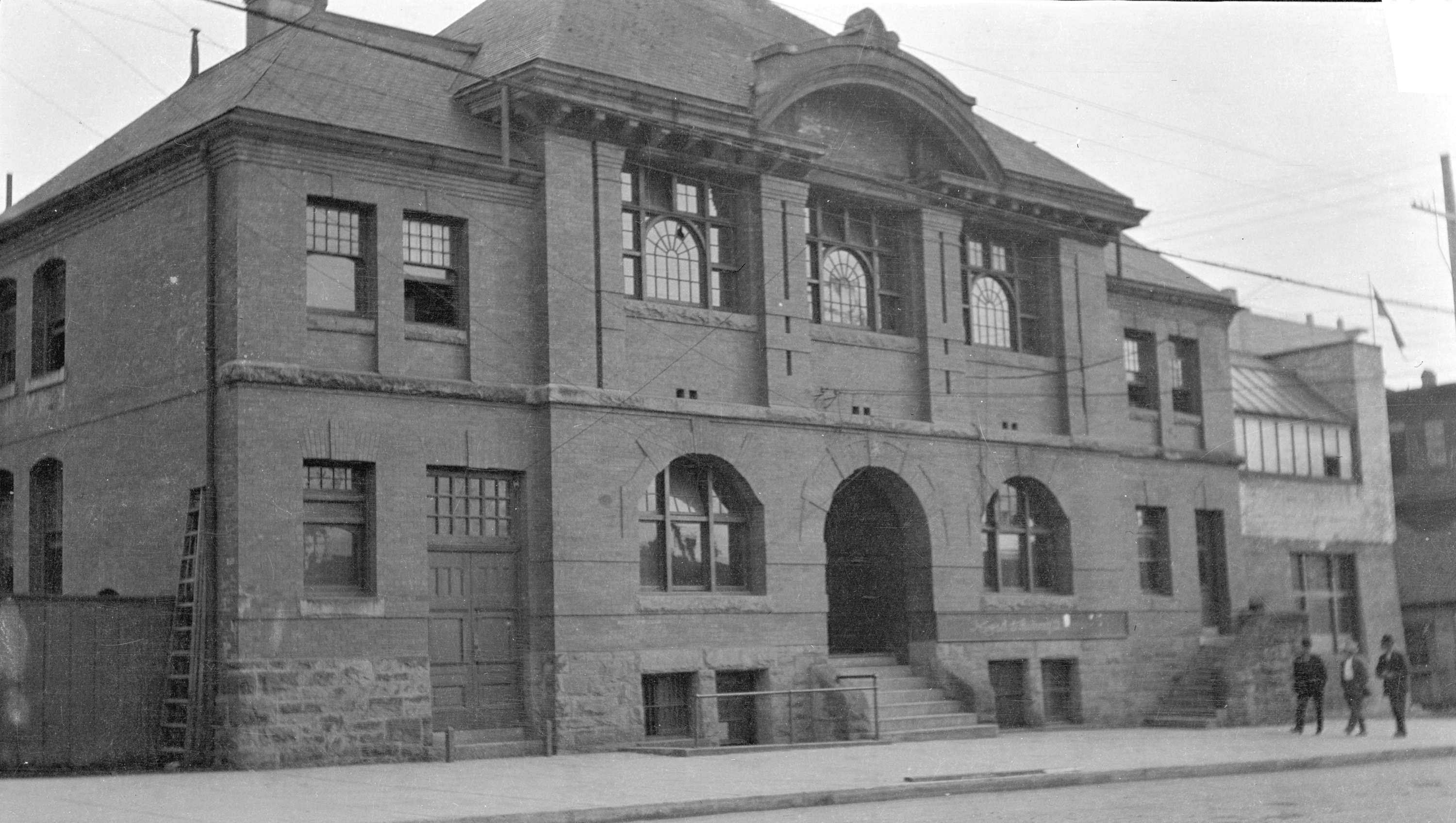

Image credit: M. James Skitt Matthews, public domain

During the Depression, we were relatively well off. My mother and father were always involved in the community and my father was a leader in the community, responsible for the power supply and dams. In a couple of the smaller communities my father organized everyone to buy whole carloads of coal, which was extra special for people struggling to stay alive. Purchasing a carload of coal costs about 10% of the regular price, so everyone in the community received coal. He built a skating rink on his own in Albert Canyon and a toboggan slide up the mountain, installing gas lamps up along the run. He was also the caller for local square dance. I must have inherited my social conscience from my father, because I belonged to the CCF, and I was subjected to the values of party which is now the NDP. I used to hear my mother and father talking about politics and they always worried about other people in the community.

Image credit: Jack Lindsay, public domain

Adolescence in Vancouver

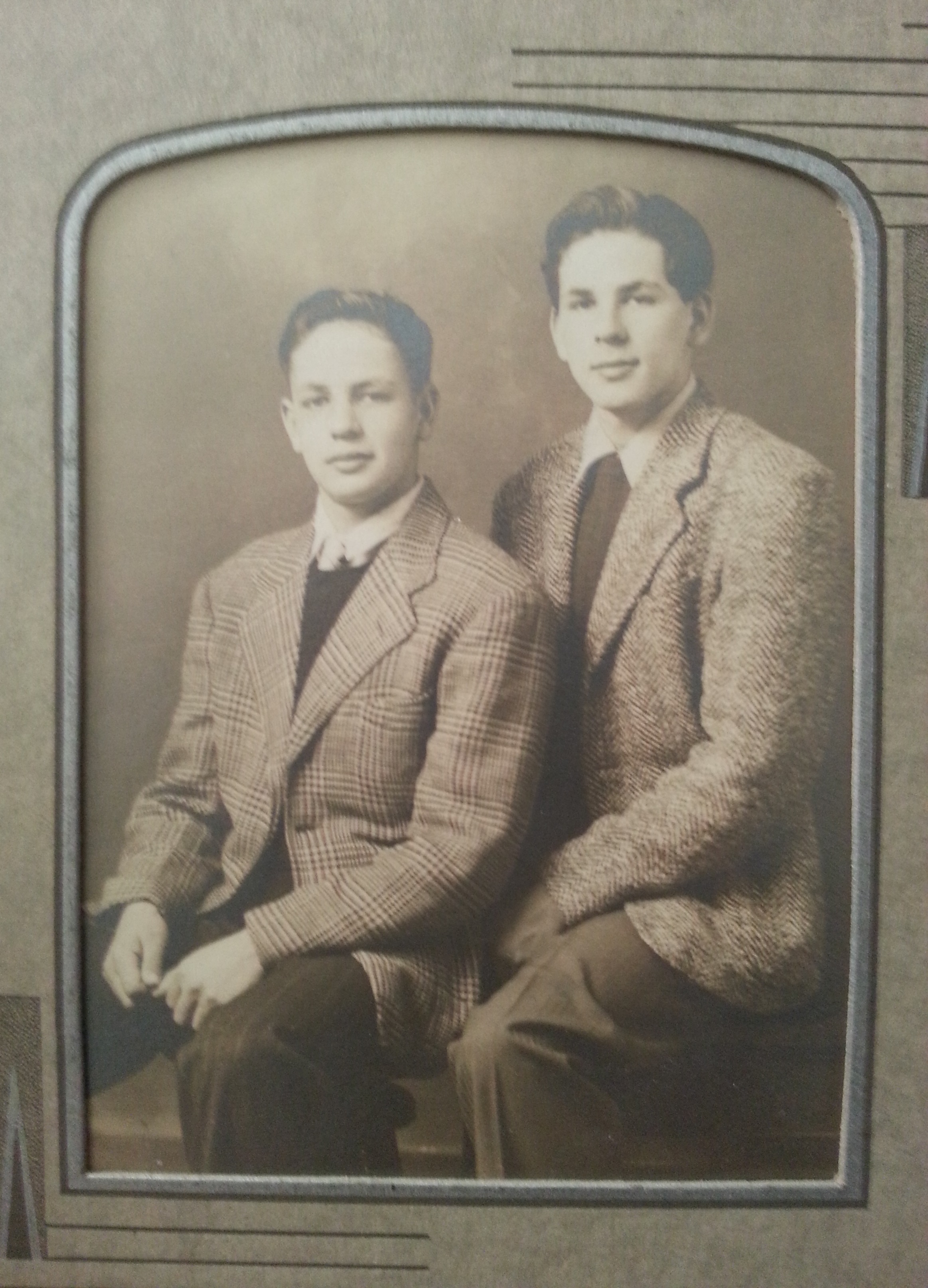

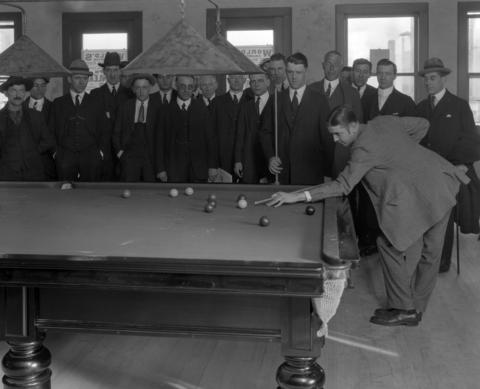

When I first came to live in East Vancouver at the age of 15, I didn’t join the political scene right away. Instead, I got into trouble, finding the pool room on 3rd and Commercial Drive called Grandview Recreations. I hadn’t played pool before but I became a real pool shark. I was one of the better players on Commercial at that time and I got into the money games; I suppose I could have made a living at it but I didn’t have any intention of becoming a pool shark. The types of people that were there were just ordinary working people, although I knew a couple of criminal types. As a matter of fact, I became really friendly with the Lawson family. Monty and Vance Lawson had been in and out of prison themselves but Bobby Lawson, who was my age, wasn’t into anything criminal. We played every day for an hour or two and I was one of the persistent winners, but I was careful I didn’t overdue it and put all my earnings in the bank, determined to go continue on to university. At that time, university was far reaching, remarkable for anyone to even think about it.

Image credit: Stuart Thomson, public domain

The first place I lived in Vancouver was in the Downtown Eastside. There were a few old cheap hotels at that particular time, and I stayed one night and realized I didn’t like it. That particular hotel was full of bed bugs; I had never experienced bed bugs prior to that. So that was an experience for me. I didn’t sleep much the first night and decided to move up here to Commercial Drive. I’ve lived around Commercial Drive on and off since.

Image credit: William Eadington Graham, copyright City of Vancouver

Commercial has always been the way it is now—although it has progressed a little bit. The bowling alley has been there a long time. Lots of little food outlets come and go. When I was 16, I took my girlfriend to Stanley Park when she came to town from Revelstoke. Main and Hastings was also where all the night life was—Smilin’ Buddha Cabaret, for instance, and the theatres. Everybody wore suits back then and the best stores were in the Downtown Eastside – Eaton’s, Simpsons, Woodward’s. The Downtown Eastside was the main centre of town, and when Granville started to develop it pulled all of the businesses out of the Eastside. Sometimes it makes me feel really sad when I see the change that has taken place there.

Image credit: Roland Tangao, CC, Flickr

Image credit: M. James Skitt Matthews, public domain

Work Life

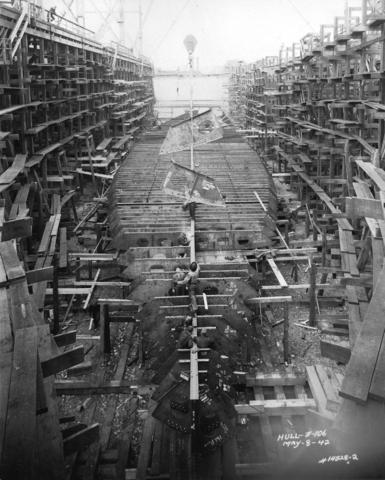

The first place I went to work was in the shipyards. There were three major ship builders in Vancouver at that time—North Van Ship Repairs, Burrard Dry Dock—which had two different locations, one in the North Shore and one on this side—and the West Coast Shipbuilders. This was one of the major places in Canada where they built ships. During the War it had moved out here from the East Coast. They were the biggest vessels built at that time in the world. I’m surprised that the whole industry disappeared and moved back east. The wages were not that bad; I think I started working for about 27 cents per hour, which was a high wage back then. By the time I quit I was earning almost a dollar per hour. I first worked at North Van Ship Repairs and then the following year moved over to Burrard Dry Dock, because I had to go back and forth on the ferry to work every day. I lived on Commercial for a number of years while I took my apprenticeship for painting and decorating to get my ticket.

Image credit: M. James Skitt Matthews, public domain

Image credit: M. James Skitt Matthews

Racism in Vancouver Schools and Court

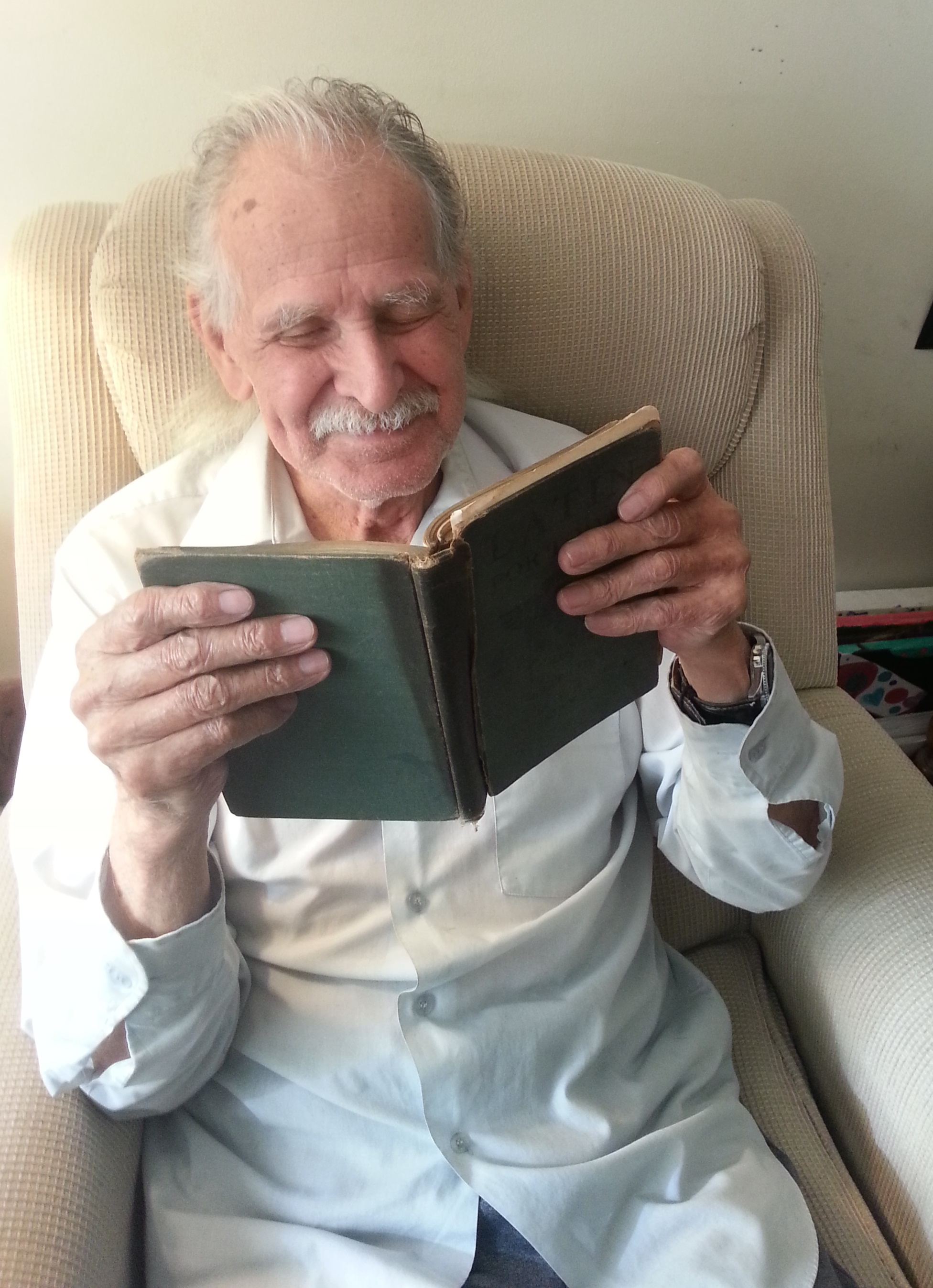

Eventually, I decided to go back to school and ended up at Britannia. I’ve still got my Latin book! Britannia has always been a bit racist, so it was a little tough for me because I was one of only Indians at that time. Residential schools were still alive, but my mother had been in residential, as well as my grandmother, and she flatly refused to have the church take away any of her children. As a matter of fact, during the time my grandmother was in residential school, the smallpox epidemic hit and her whole family was wiped out except for herself and her brother who were in school at the time. At that time, they graduated residential school at 16, but she had nowhere to go, so they kept her on. That’s where she met my grandfather, who was one of the few Aboriginal traders and fur buyers in the 1800s.

Image credit: M. James Skitt Matthews, public domain

I was abused all the time by all the different teachers at Britannia. As Indians, I guess we grew up a little different because my father earned good wages and we were sort of elite in the community. I came here with that attitude, so it was hard to put me down. It sounds awful, but I had already concluded that I was better than other people! I wouldn’t put up with the racism, so I quit. Then I got into trouble and I wound up in jail. I received six months and it was a phony charge—vagrancy, of all things. I realize now it was because I was an Indian. After all, I had a job and a place to live!

I just happened to be out at 11:30 at night. There were three of us out looking for cherries. We knew of a cherry tree in an alley around Nanaimo and 14th, which is where we got arrested. That ugly little cherry tree in the alley. I wonder if it’s still there—I haven’t been curious enough to go see. I’d go and chop it down! I ended up getting convicted and I appealed the conviction and got out on bail. I moved to Abbotsford and went to the high school there, although after about only a month the principal called me in and asked me to leave the school. I was an excellent student, probably one of the top students at the school. I asked him “Why? You know my grades are good and I’m working hard.” And he said “No, you’ve been in jail!” So I told him the story and he said “It doesn’t matter; you’ll contaminate the rest of the students.” So he threw me out of school!

Image credit: M. James Skitt Matthews, public domain

That gave me a jaundiced attitude; after that, I was an outlaw. I was angry, so I went a little haywire after that. I got sent back to jail on the same charge and went to county court for a new hearing. What happened was the judge had got sick; something was wrong with his throat and he couldn’t speak. He was off the bench for three months and I was on bail that whole time, waiting for the hearing. The day he got back to court, I was the first order of business. He said “This has been going on long enough! I’m sick and tired of this case.” I had only been in front of him once before that and none of the information was presented. Nonetheless, he said “I find you guilty and re-sentence you to six months.” So when I went back to jail. One of the guards who talked me into appealing the charge in the first place couldn’t believe I could be back in jail again. He told me the only option I had now was to write to the Solicitor General in Ottawa and lay my case in front of him. So I did.

I had 13 days left on my six-month sentence when the guy who was in charge of our gang came to me and said “Lightbown, you got a parole.” I said “No way, I got 13 days left. I’m going to finish my time!” I was really hostile. So they sent me back to my cell and around 11 o’ clock the guard came and said “Get your stuff together. It’s not a parole; it’s an unconditional release.” So I said “Well, I’ll take that.” I received a letter from the Solicitor General. It was quite a long letter and in it he said “I can’t give you back the time you’ve spent and what you’ve been through but I can assure you that your record and your fingerprints have been removed from record.”

Escaping from Prison

I learned all kinds of things criminals should know and I even broke out of prison twice—I’m the only person to break out of the downtown police station at Main and Hastings. I sawed my way out. When I was on the loose prior to that I figured I was going to get arrested sometime. So I had hacksaw blades sewn into the sides of my shoes. The cells were on the 3rd and 4th floor. I started the hacksaw on the bars and pretty soon I was bleeding from every finger on my hand, right to the bone, but I managed to cut and pull the bars down. I had made a rope out of all the mattress covers in the cells on that floor and I slid down.

Image credit: M. James Skitt Matthews, public domain

I stopped in front of a big window on a floor with all the detectives and reporters working and walking around. I dropped pretty fast after that! It sealed all the cuts on my fingers, cauterized them, so I quit bleeding by the time I hit ground. I ran out onto Hastings Street. I had two bits—25 cent pieces—which bought four streetcar tickets. A streetcar was about to pull away, so I jumped on. Before they even knew I was gone I was blocks away.

Working as a Car Salesman for Jimmy Pattison

I made friends up here and I got to know a lot of the people. For instance, Jimmy Pattison came from this area and I worked for him later on in my life as a car salesman. I liked working for him but he had some very strange habits. I know for a while that every month one of the car salesmen got fired—the guy lowest on the sale totem pole in terms. I felt maybe that’s when my social conscience really began to develop because I felt that was an unfair tactic. Actually, I got a call the other day from a fellow who I hadn’t seen since we worked for Zephyr Motors on Broadway, about 60 years ago, when I was around 20 or 21! He reminded me how I helped him when we first started working together; he had a difficult time selling cars so I gave him advice. He now works for C-SPAN. He had apparently run into someone from Haida Gwaii and somehow my name came up and he gave him my phone number.

Love and Politics

Lavina has been a part of my life for 62 years and has had a great influence on the directions I’ve taken. I met her at a party in Prince Rupert. I had landed in town to work and our boss had a girlfriend in Rupert, whom he contacted right away. There were six of us in that crew and we did the town in one big shot. She said to me “ Have I got the girlfriend for you!” I said “What the heck—okay,” and she introduced me to Lavina. We took to each other right away and we’ve been together ever since.

Lavina had been married before. By the time I came along, they had separated a couple of years and had a few kids. She took me back to Haida Gwaii to meet her family and I got along really well with her mother. She had a big family and all three of her brothers had fairly large fishing boats which fit six people—as big as they got back then. Lavina and I were both commercial fishers. Lavina is the granddaughter of Charles Edenshaw. He was probably the best known Aboriginal artist in British Columbia at that particular time. All of our children were artists. Bill Reid came along later, then Robert Davidson and, of course, Beau Dick, my daughter’s husband. Their daughter—my granddaughter—got her artistic talent from both sides of the family. At one point Lavina and I developed a market for Aboriginal art in Vancouver, and one of the things we did was travel down to the States to put on art shows. We went to a bank here in Vancouver and we got a line of credit for $300,000, which was a lot of money back then. The banks had a lot of faith in our ability to promote the art form. Lavina also designed eight different designs for the city banners—I remember her arguing with the city manager over the colours. Even at the last minute he was trying to make her change the colour, but Haida designs have a particular colour scheme. The day they put them up he was still grumbling about it.

Image credit: Mike, CC, Flickr

Image credit: JohnnyCerveza64, CC, Flickr

We lived in so many different places in Vancouver. We were kind of fussy where we lived because we felt it was necessary to give our children an opportunity to make their way without having to tough it out. We never did go short of anything in our lifetime because I’ve always been a good hustler and Lavina has been an exceptionally capable person, always earning money at something. She had an art store in the Royal Centre, and the classiest ladies’ store Prince Rupert ever saw. All the stores were a bit junky when we moved there. We bought from a supplier in Vancouver, so it forced stores up there modernize in order to compete.

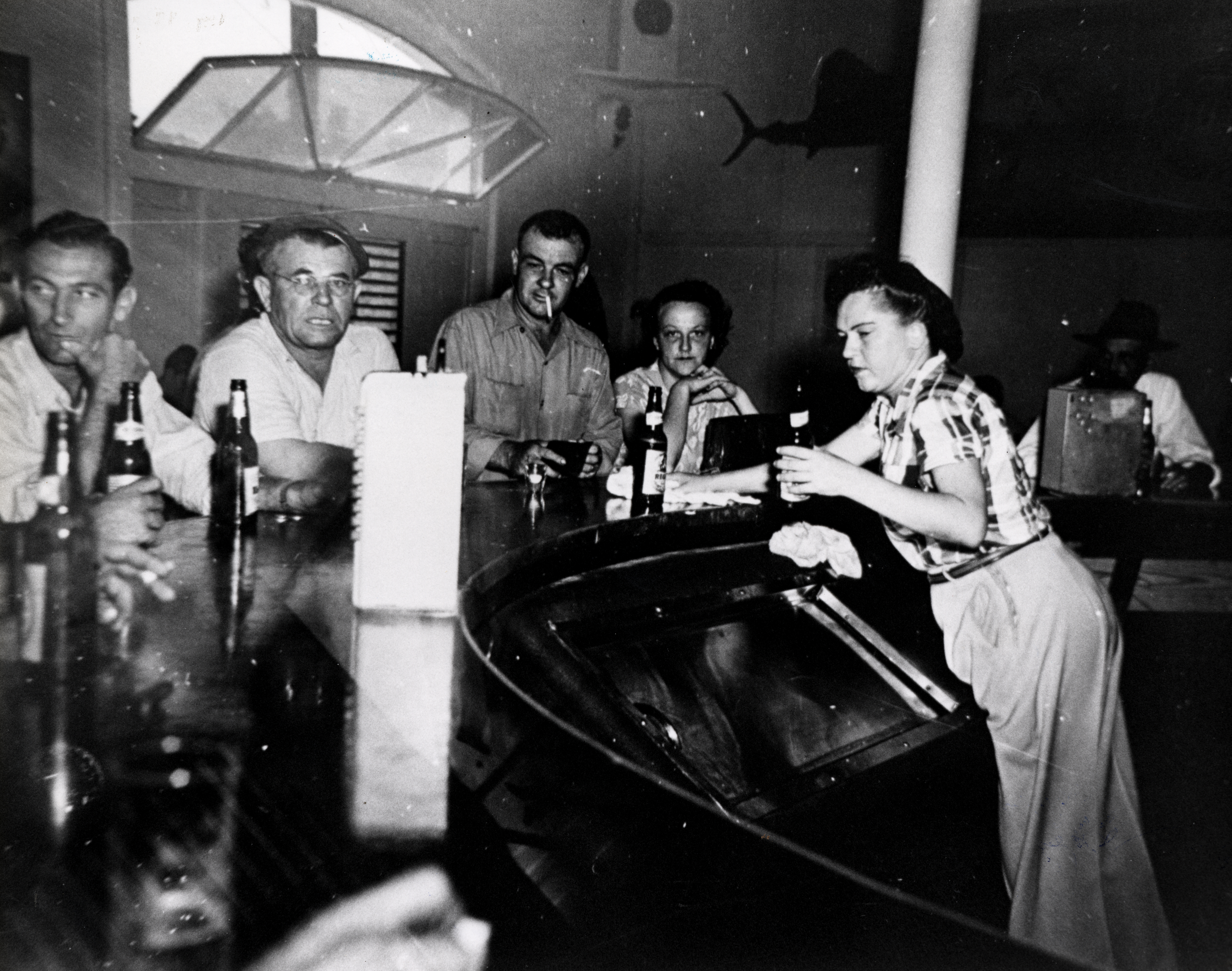

One of the things we did was run a booze can. That was part of the scene at Vancouver at the time. There were a number of speakeasies and after-hours places—all illegal of course—on Granville Street, and a couple in the East End (in what is now the Downtown Eastside). Most of them were upstairs, with businesses down below. After what happened to me when I was young, and as time went on, I always worked against the laws and rules and regulations—especially the ones put on Aboriginal people. We opened one just off Granville St. and it was so successful that there were two or three business people who would come there and try to talk me into selling it to them. I eventually did, and then opened up another one over on Thurlow. We rented the whole house; it was a big house, and became twice as successful. All the people from the nightclubs used to come—the performers too—and we had big parties. The cooks used to bring food, so anyone who came to my booze can would know they were going to be fed and entertained. It was a pretty popular place and the police used to leave me alone. Every once in a while they’d give me a warning to let me know they were coming to knock on my door. Of course, when they came in, the place was packed. I asked the guy who was in charge of the dry squad why they were leaving me alone and he explained: “Because your place is so popular,” he said, “We know if we’re really looking for somebody, we can just watch your place until they come.”

Image credit: Florida Keys–Public Libraries, CC, Flickr

The CCF was not very strong in the ’50s and ’60s; we had just come through a war and you know it’s very much right wing governments that support war. The NDP was very supportive of the existing governments at the time, but they were beginning to gather strength. At that time there weren’t any Aboriginal organizations outside of the Union of BC Indian Chiefs (UBCIC), which was, in itself kind of limited in its scope, as it only reflected reserves, not any of the off-reserve people. We lived on the edge of Shaughnessy Heights in a huge mansion. The grounds were about a block long, with a fish pond and a big lawn. That’s where we were when Butch Smitheram came along when the Secretary of State first made money available to Aboriginal political organizations so we could organize ourselves. The prime minister at that time was supportive of the Aboriginal people finding their own way and being able to fight back. Butch Smitheram was a Shushwap Indian, working for the Secretary of State, and they sent him out here to organize in BC. We spent a couple of days establishing what became The BC Association of Non-Status Indians (later the United Native Nations). Together we started organizing on the basis of the right to full ownership of land. Before then there was not a lot of discussion about things like that, so I was one of the original sovereignists.

I guess I’ve done a lot of things that most people don’t know anything about, and I never ever felt it was necessary to tell people my accomplishments; so just being handsome is good enough! Haida Gwaii is home for me. I’ve traveled to Kootenay country—where I’m really from—on a number of occasions, and I do have lots of relatives up there. But my real family—the family I married into—is on Haida Gwaii. That’s where I feel comfortable and where I spent a good part of my life in my older age. I fished the whole coast- halibut, herring, all different types of salmon, oolicans… What kept me here in Vancouver was my involvement in the struggle for the recognition of Aboriginal people and their rights. I really couldn’t fight it from way up there; I had to be where the action was. Lavina is in Haida Gwaii now and she was really happy when I went back up there to stay with her for about 10 weeks this past summer. If it weren’t for my health, I’d still be living there. I don’t have the energy that I used to so I know it’s time to move on and hopefully I’ve passed on something to somebody.

Image credit: James Crookall, public domain

Story edited by Jade McGregor

Leave a Reply