Five Longshoremen Discuss the Shipyards and the Unions

Longshoremen Dave Lomas, John Cordocedo, Arthur Marshall, Les Copan, and Frank Kennedy share their experiences as members of the International Longshoreman and Warehouse Union and make predictions about the future of Vancouver longshoring. Frank Kennedy passed away in late 2014.

Leni Goggins: I want to know what you did for the port generally, what gangs you worked on, and your specialty.

Arthur Marshall: My name is Arthur Marshall. I started on the waterfront down at the CPR docks in 1945 just after getting out of the services and retired in 1986. I worked at Pier A1, 2B and C, shared five, six and seven and pushed a hand truck, which was a tool of necessity in those days. I worked hard, very hard; it was a lot of hard work all the way around. I lasted there about five years and then I left and became an International Longshore and Warehouse Union member. That’s about it for the rest of my services.

Image credit: Price Family, public domain

Les Copan: My name is Les Copan. I started on the waterfront in 1953 and retired in 1988. In the first week I worked three days: the first one shoveling wheat, the second one discharging Japanese oranges—which in those days was a real rough job because they had ’em all wrapped, two boxes bundled with that straw rope and then strips of wood between to keep them from moving—and the third day I worked on sugar. 240 pounds of sugar, a real introduction to being a longshoreman. That was a tough one, but I survived it and, as I say, I’ve had 35 years of work and 23 years of retirement.

Frank Kennedy: I started in ’51 at the Coastwise Local and retired in 1990. At that time, at the Local, we had to work around the clock or around one-and-a-half times without stopping and getting a new gang. I had been on the boats before, so long hours didn’t do me any harm. For most of the guys in the Coastwise Local, their one desire was to be a member of the Local 501 at that time because there was more stability in that local. Eventually that happened.

Image credit: Jack Lindsay, public domain

John Cordocedo: My name John Cordocedo. I started on the waterfront in 1952 and I retired in 1996, after 44 years. I came out of a logging camp, and it just happened that logs where moving here so I got on the waterfront working as a boom man. I was just in the later stages of the real physical labour down here; that ended in the mid-’50s and from then on life became better when automation moved in. Over the years there, I guess it has seen a big change in this waterfront, from then to the present. Other than that, it’s been a great ride. I was also in the original longshore deep sea Local 500. Local 500 is the result of amalgamation of seven locals here in Vancouver and we put ’em all into one.

Dave Lomas: My name is Dave Lomas. I started working on the Vancouver Waterfront in 1959 and I retired in 2004. In the last 20-30 years they used to hire extra people down on the waterfront because of Christmas. I started on the hand-sawed lumber. We went on a ship and started from the skin, working all the way up to put a deck load on it for up to 18, 19 or 21 days, just working one ship of lumber. For the first seven or eight years, I worked down here as a causal that’s basically what I did, mostly lumber and grain trimming and handling sacks. Mostly heavy work.

Image credit: Major Matthews James Skitt, public domain

Leni Goggins: A lot of you mentioned the union. You came in when the ILWU was established. In the beginning stages, there was a lot of fights fought to get benefits for longshoremen. I was wondering how the union affected the job.

Les Copan: Oh, it gave us control. For example, the first pension came in 1953 just before I started. It was employer-funded, so they called the shots. In 1958, we had a strike for 28 days; the main thrust was to have a say and control of the pensions. That was one of the major achievements because we still have fifty-fifty say in how our pensions are funded and handled. On the job we were able to tell the employers that we were working too hard because, prior to 1959, our collective agreement specifically stated that we might not have mechanized equipment aboard ship. In our ‘59 contract we eliminated that clause and they immediately put lift trucks aboard, which made a major difference in our lives. With mechanization and packaged lumber—instead of carrying it stick-by-stick—they they put it in bundles of 2×4 with varying lengths.

My understanding is that packaged lumber came about because of the Korean War; the American ships couldn’t get their ships into dock and had to anchor in the bay so they threw the lumber overboard. Then someone got the idea that if you made a bundle of it, it made it easier, and it certainly made it easier for us because we put a lift truck down the hatch, which did the back work. They even started putting general cargo on pallets and, of course, eventually containers were introduced. The difference from when we started and when we retired was very, very large.

Frank Kennedy: When I first started longshoring, the Coastwise Local was a member of the ILA, not the ILWU. It took until 1954 to finally come into the ILWU. That three years was just a continual argument amongst the guys about whether or not we should belong to the ILWU or not. The ILWU was in most ports up and down the coast. A couple were still waiting it out. But that was the big move we made in the Coastwise Local. It didn’t change the work habits or work opportunity; it just changed the basic feeling of security on the job. As I said before, it was something that a lot of the guys had been waiting for since 1935. They couldn’t wait to get out of the ILA and into the ILWU.

The first container operation in Vancouver was Whitepass, Yukon; they had a steady run from Vancouver to Skagway. There was all containers, except on the deck, which could be loose cargo (like steel or something). That operation became successful because they had the only cargo going up North, and all kinds of things were going on in the North at that time. Then they’d haul it back to Vancouver—the famous cargo asbestos. That was an enormous amount of work for the longshoremen. They lost that but they found other ways of making the whole operation work. That was the most successful container operation; they couldn’t even get that good of an operation during the Vietnam War. They had lots of cargo going over there, but all they had coming back was empty containers. Well, in White Pass they didn’t have to worry about that, because they had them full both ways. That’s still in operation.

Image credit: Walter E. Frost, Copyright City of Vancouver

Arthur Marshall: Before the container operations, one of the biggest advantages in working the waterfront was to get away from the hand trucks, with forklifts and palletized cargo. That was a big big change I could see in the sheds due to stockpiling cargo many tiers high, which took up less space in the sheds. As I said, it did away with the hand trucks, which was a big change at that time.

John Cordocedo: I did mention that the first containerization was Coastwise Local. That was the best unit per man-hour labour on the whole coast. It was a little operation with only one ship at that time. It’s been a big change from there on in. You think of palletizing just as one example, sugar, which Les has mentioned. 240 used to go up to 280 sacks. One day we’d do those by hand, with one guy on each end, and they’d have to lift it, put 12 sacks together and then take it out on a sling and put it on the dock. The Rogers family finally turned around and saw that that was too labour-intensive so they put it in clems and brought the sugar in bulk, which is how you get it to this day. That’s a long time ago.

Les Copan: On a personal note, containerization changed my life. When they first brought in the deep sea containers, they had straddle carriers which the employers decided only their regular employees could drive them. Pretty soon they discovered they needed more men, and I was the second person from the dispatch hall to be trained on the straddle carrier. They sent one of the regular employees up with me on the machines, showed me what to do, sat with me for a while and put me on my own. The second day, they gave me a straddle carrier and told me to go out and practice. About halfway through the afternoon, when I came down for coffee, the superintendent of the dock said that I was doing OK and rated as a straddle carrier driver, so I could go home. As there were only a few of us that were rated, we worked continuously. I made a big living, a good living, and it was a very easy job. So it actually made a change in my lifestyle.

Leni Goggins: How do you think the port affected the development of Vancouver as a city?

Frank Kennedy: If it weren’t for the port operation, we’d have a bunch of condominiums along the waterfront. That’s been a problem the unions had to face with from time to time. Someone will come along and want to build an operation on the waterfront that has nothing to do with shipping. And you have to do what you can to get them to change their mind. It would be a drastic change if anything ever happened—if they shut down the Second Narrows Bridge, it would be the end of moving everything out to Roberts Bank.

Image credit: Walter E. Frost, public domain

Dave Lomas: The port of Vancouver energized the economy of the whole country. When they opened up regular trade to China and started building new docks, new container cranes and new equipment on the Vancouver waterfront, I could imagine that it increased the throughput of goods into Canada tenfold. It changed the politics in B.C. because of the big money involved. It changed the Vancouver Waterfront with the new docks that were built. The grain facilities that were put into Vancouver also energized the economy of the Prairies.

John Cordocedo: It’s a very political subject you’re talking about. The Port of Vancouver was starved out of funds when its predecessor, the National Harbours Board, just happened to be building Fort William and expanding the Saint Laurence Seaway. I don’t think there was much financial gain out here for the port to develop; as a result, the employers were somehow mixed up in this because they didn’t go public on it. I remember when the containers started, the first container ship. We had two cranes! A lot of us sitting around here today lobbied with the federal government for more equipment. It was a one-sided plea because the employers didn’t see one side; you know how politics are. Someone was doing some lobbying back there, saying we had to wait until it moved on, and now we have adequate cranes here.

Dave Lomas: I hate to contradict John, but they built one crane here. They put in one crane, and the port was run from Ottawa in those days. They leased out that crane to the Japanese “Big Five,” which meant they had priority in getting it unloaded. I actually saw instances where there was a ship that was other than the Japanese Big Five lines, and when one of their ships came in, the other ship had to stop, go out and anchor until the Japanese ship was finished. Then they could come back and finish theirs, which of course was very expensive for the one that got pushed out of the way. That helped greatly in convincing the government that they needed more cranes out here.

Image credit: Major , James Skitt Matthews, public domain

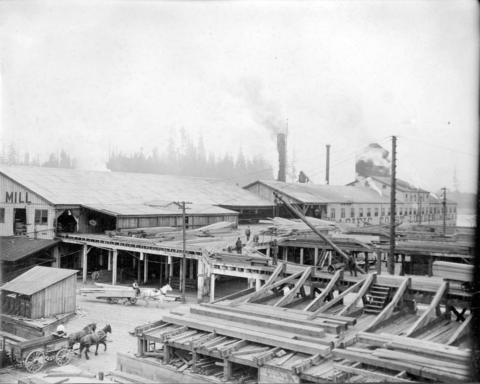

Leni Goggins: We’ve heard a lot of stories about how the roads used to be paved with wooden slats and tar. Now those are gone, as well as the streetcar (except the one out there), and the the lumber mills. Do you think Vancouver is disappearing?

Image credit: John Davidson, public domain

Les Copan: When I was a preteen, we lived at 12th Avenue and St. Catherine’s. The False Creek flats were the railway yards and the city dump, where we used to go down and play. There was a roundhouse with locomotives, and we climbed up on the locomotives until the city workers chased us out. As they filled in the city dump, they put in six inch timbers for the trucks to run out on, and of course rats took refuge underneath. We used to go down and watch the guys who had dogs called “ratters.” It was a real sport; they chased the rats out and then the dogs chased the rats. That whole area has changed, and one of the major changes was putting in the overpass. We were at the opening when they opened the street across and they filled in the False Creek flats completely. You’d never know that the railway used to be there. Arthur mentions working at the CPR, but he didn’t mention Pier D.

Image credit: Philip T. Timms, public domain

Arthur Marshall: I didn’t mention it ’cause it burned down.

Les Copan: You never saw it. There was a pier next to what is now Canada Place. There was a pier there that the CPR used exclusively for the their ships running to Nanaimo, Victoria, and Seattle. In 1939 it burned down. On that day, my brothers and I had been down at Stanley Park and, as we were coming home on the streetcar, we saw the smoke and we got off and stood around Granville and Hastings watching. We watched it burn for two hours and, when we went to get back on the streetcar, we were concerned that we had a transfer. We asked ‘”s he going to let us on?” The conductor looked at us and said “You have been watching the fire, no problem, get on.” That was a major factor in changing the waterfront of B.C. because it took that whole thing out and they had to move their passenger ships to Pier B.C., which is now the Convention Centre. Younger people today have never even heard of Pier D.

Image credit: Westcoast Transmission Company, copyright City of Vancouver

Frank Kennedy. Vancouver will never disappear; it’s the hub of the whole of Southern British Columbia. Even though the papers say that other municipalities are thriving and Vancouver is stagnating, it doesn’t really tell the story. Vancouver is thriving just as much as any other municipality and will continue to do so with the present issues that are existing with cargo. There’s an increase in the movement of containers, of all cargos. It’s not only the container docks that are in operation—there’s sulfur, ore and woodchips. The port will always be here.

Dave Lomas: A lot of younger people nowadays wouldn’t know when I mentioned sheds 5, 6 and 7—they also burned down. Since then, they put that park there on the waterfront, which benefits a lot of people in the East End. It’s a nice little sport for people to look out and look on the harbour.

John Cordocedo: If we go the way things are happening on the North Shore… I was born and lived all my life on the North Shore. They built a hotel where we had the biggest shipyard on the west coast, next to Esquimalt. If the policy of the local politicians is that they’re going to build condominiums where there should be a workplace, and industry, that portion of the North Shore will probably go. But I think with the advent of young people coming up, it’s going to be up to them to work that out. It’s no good living in a condominium in the Pinnacle Hotel if you don’t have any work. It’s that simple.

Leni Goggins: Young people my age, when we say longshoreman, we think of Marlon Brando. On the waterfront, they think of the stereotypical longshoreman who is foul-mouthed and tough as nails. Do you think there is some truth to the stereotype?

Image credit: Insomnia Cured Here, CC, Flickr

Les Copan: At one time, longshoremen were known as a bunch of drunks and thieves. As in any industry, there were some who were drunks and there were some who were thieves. I saw just the other day that Canadians lose something like $6 billion in internal theft. We weren’t different from other people; for the most part, we were just hardworking guys who went home and played with our kids and enjoyed life. The Vancouver I knew as a youngster has disappeared, but it has grown into something better. I look at these guys and I think we’ve changed as much as the city has changed, and things will continue to change. John mentioned politicians; if you let them loose, they do major harm to the longshore industry. Where else can you land cargo on the coast? There’s only two areas, this one and Prince Rupert. Prince Rupert is booming because here in Vancouver we’re two days closer to Japan than Los Angeles, and Prince Rupert is 500 miles west of Vancouver, meaning a container can be landed there and in Chicago before a ship can get into Los Angeles. The changes are going to be dramatic; however the world changes, we will change with it. If we have another depression, things will be tough and won’t change for a while.

Image credit: Major James Skitt Matthews, public domain

Frank Kennedy: I think you want us to concentrate more on the relationship between the young people and union. Maybe they don’t belong to the union. I don’t think we have too much to worry about. Some people seem to think the young people don’t care what’s happening in the union. We had a couple of occasions last year where we drew some of the young people out and they participated in organizing and participating in the event. That was the 75th anniversary of the Valentine Pier and we had a great extremely good turnout of young people. We took that same event to Prince Rupert and celebrated the 100 year of longshoreing in Prince Rupert. Even though it’s a much smaller port, we had an excellent turnout of people, mainly young people. Young people care about it.

There is one thing young people don’t like, and I don’t blame them for it. Like Dave mentioned, he was six years on the spare board and he worked his way up the boards. Well, in my mind, that’s not necessary to have people waiting that long. There was one period where there were quite a few more people needed than was available, so they took people down to four or five years seniority. They probably should have kept that up. It bothers young people to think they’re second-class citizens. Someday maybe they’ll get around that problem. There’s a chance of employment, and the union protects the rights of the casuals. In the long haul, I think the younger people are concerned. They may say “the hell with the union” from time-to-time, but we’ve all said that.

Image credit: Donn B.A Williams, public domain

Dave Lomas: I think the image of the longshoreman as a drinking, brawling, fighting person is still alive and intact today. The only thing is that it’s a different gender because we have more females down the waterfront. Because of that, the waterfront has changed. It’s changed in the last 10 years; some of us here were already retired when it changed. Maybe the image the people outside have is still the same, and there’s nothing wrong with that; it’s part of the pride of the longshoreman, the swagger. The other part about the younger people—do we have any faith in them? A lot of us have been doing a lot of research, because not enough research was done in the past about longshoring back to the 1800s. What we’ve been doing with that research is teaching: talking to young people in schools, doing seminars and publishing material about the history of the union. Many people I talk to are in the same position as I think longshoreman were years ago—they’re just learning and, once they catch on to what the unions are all about, they join in and participate. I think that this organization has a great future.

Conversation edited by Jade McGregor

Leave a Reply