Shirley Chan: “I Cried Because I Lost My Library”

Shirley Chan (b. 1952) grew up in Strathcona. She reminisces about her childhood games and the pain of losing her beloved neighbourhood library.

TEXT VERSION

My name is Shirley Chan and I was born in Vancouver in St. Paul’s Hospital. A few months after my mother returned to Canada from China, where she spent her early life—she was actually born in Vancouver too but her father took the family back to China when she was 8 and sent remittances back to support the family. We lived in Strathcona for most of my life; my father arrived in Canada when I was about two years old and we moved into Dunlevy street, just off Keefer, where my family rented a home. Then my grandmother and my sister, who is ten years older and was born in China, came and joined us. We lived in Strathcona from the time I was about two and we were evicted from our home on Dunlevy because of the city’s plans to build public housing at MacLean Park and demolish that neighbourhood as part of the phases for urban renewal in Vancouver.

I used to play with the girls from across the street. One of the girls had a family store… right now I couldn’t even tell you where that store is, I guess I should look up some historic documents to find out. My dad worked in Chinatown which I could walk down to Chinatown to see him.

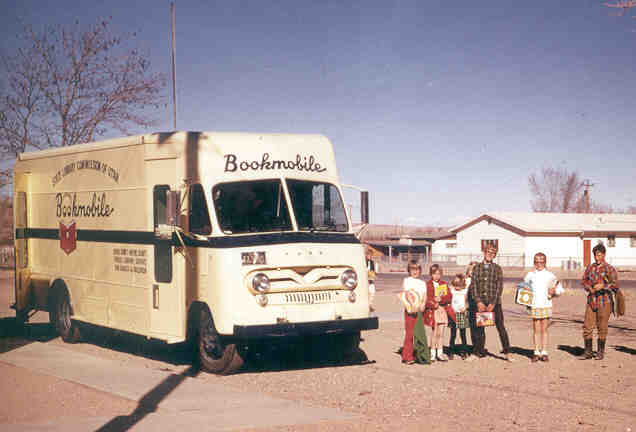

One of the most important resources in this neighbourhood growing up was the Carnegie Centre, where the museum and the main branch of the library were, in the main branch. I remember that, when they decided to moved it to Burrard, I cried because I lost my library. They brought Bookmobile, but it wasn’t the same. And being able to go there, which I did almost daily. They allowed me a maximum of four books, and I would borrow those four books. They were treasures I took home because they were my escape from this neighbourhood and also from the daily grind, because I had to babysit my siblings, as the eldest of three. I had my grandmother, who didn’t like me very much, because I hadn’t been very nice to her when she came. I was about three years old and told her that these were all my mother’s things and she couldn’t touch anything. We became close later but when we were younger I felt that she favoured my sister, so I liked to get away. The books gave me an escape to another world where I could learn about another world, things that I didn’t see around me every day.

Image credit: Art Grice, Copyright City of Vancouver

Image credit: Utah State Library, CC, Flickr

We loved living in this neighbourhood because we had community, safety and security; we could communicate without any problems should there be emergencies, yet this neighbourhood wasn’t all Chinese when we first moved in, in 1954. There were a lot of Italians and German-Canadians. We actually bought our home from the Minichiello family and they moved to Grandview-Woodlands. We assumed their mortgage so we didn’t take title until five years later in 1959. The mortgage was like five-and-three-quarter percent or something like that, which today sounds normal, but when I bought my first home in Strathcona on Jackson in ’81, I paid 15-and-three-quarters. That was during the days of double-digit interest rates.

Growing up here, many of my Chinese friends went to Chinese school; there’s one just over on Pender at Dunlevy. I used to go the Pender Street YMCA where they had organized programs for the children in this neighbourhood. We were introduced to non-Chinese customs, like Easter and chocolate Easter eggs—that was the big thing. We were connected with young women who were interested in some charitable work, so they helped us learn and play games. We brought home puzzles and games and things like that, from the “Y.” My sister went to kindergarten at the little church a couple of doors away from our house; the church is now occupied by an artist who lives in this hundred-foot house, so that’s quite a nice home for her.

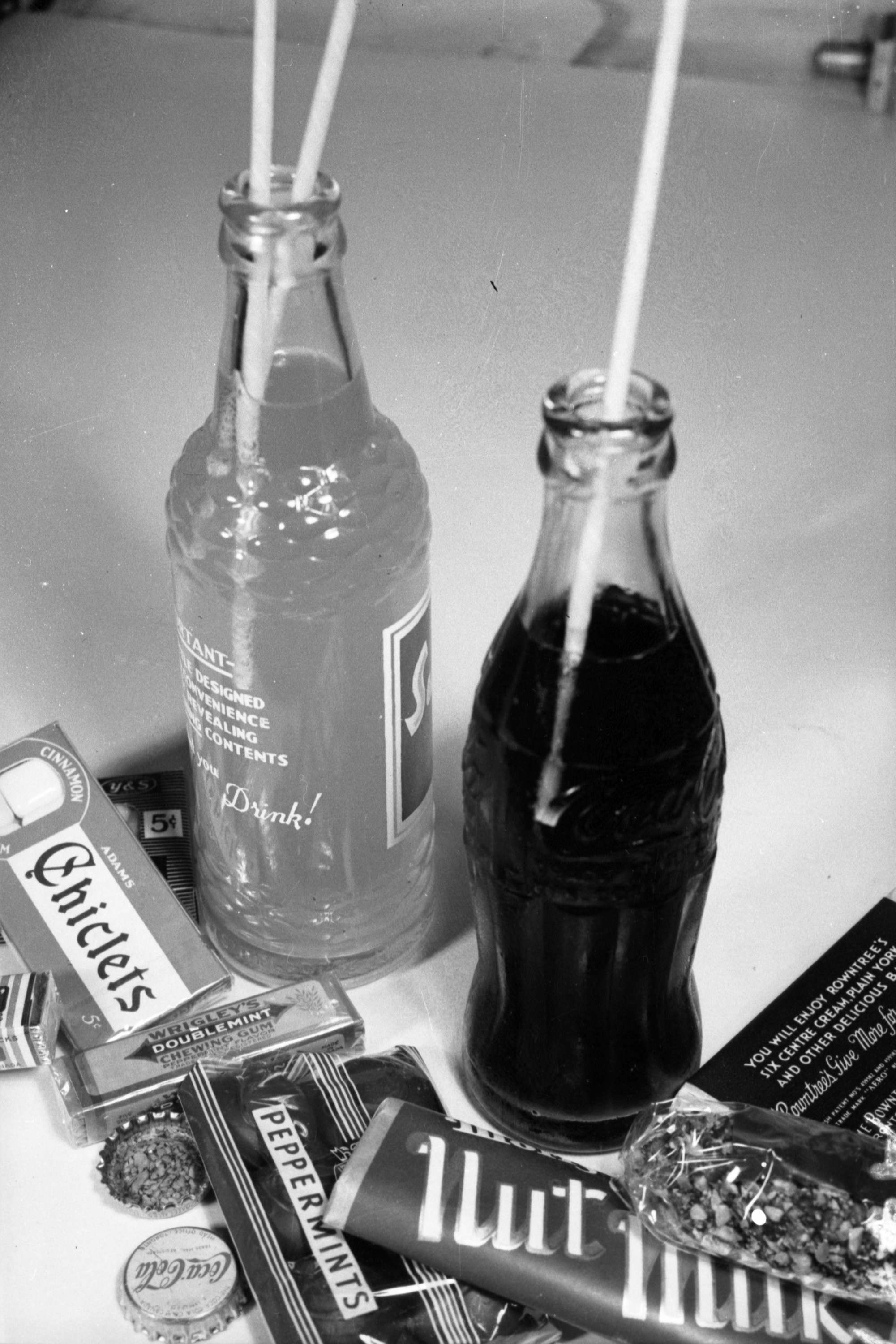

I remember that, if we got a quarter or something, we went to Chinatown to buy a bowl of wonton soup. That used to be a special treat when we went out. If we found a pop bottle, my brother and sister and I went to the corner store and traded it in, because it was worth two cents, and we could get six candies. We could get penny candies—three for a penny. We certainly felt like kings for a day when we found a pop bottle. We didn’t have a lot of spare money in our house and we didn’t get a lot of treats, but we were always well-fed.

Image credit: Jack Lindsay, public domain

We wore a lot of hand-me-downs, which was fine. I didn’t have a sense of fashion at all until high school, and my mother took me out to Fields and I bought a coat, a skirt and a blouse; those three items stuck in my mind. I went to grade nine at Britannia. Most of the time we managed to dress reasonably well in hand-me-downs.

One of my friends who had grown up in this neighbourhood said “Oh, yeah, you can always tell the girls from Strathcona because they’re all better dressed.” And I thought “Better dressed? Oh, I’ve never thought about that.” That goes to show that there were no fashion magazines, and we didn’t even have television in our house for many years.

Image credit: Vancouver Planning Department, Copyright City of Vancouver

We had a party-line phone, which caused some fiction with other party-line members when we couldn’t get through one night (we thought we saw someone lurking across the street at the gas station). That was when we were still living on Dunlevy. I remember there was a lot of excitement around that, what with not being able to call my dad and tell him to be careful coming home. So then we switched from party-line to private line.

Image credit: CRASH:candy, CC, Flickr

What else can I tell you? We used to play on the street, in the lanes, and the empty lots if there were any. My brother used to play football all the time with our neighbours because the family next-door was very large and had a lot of boys who came there. It was a home where the children of the neighbourhood were really welcome and they call gathered there. There was not a lot of adult supervision, just the older siblings who were providing for the younger siblings. It became a real gathering place, and my brother used to play football on the street with all the young men who were my age (he was six years younger). They welcomed him and didn’t say “Oh, well you’re too young to play.” They invited him, played touch football together and said “Oh, your little brother he’s so fast, he’s so little runs between our legs and makes his touchdowns.”

That house, unfortunately, burned down. I’m not sure why, someone smoking in the attic maybe. It became one of the sites where, after we had stopped the freeway at Urban Renewal fight, we focused on stopping the demolition of all our homes in the early ’60s and early ’70s. But we were able to build some new duplexes and so on; it was part of the infill housing program, so it had been a big empty lot for many years. Then it became part of the new redeveloped program that we initiated once we knew we could stay in this neighbourhood.

Story edited by Jade McGregor

Leave a Reply