Bruce Macdonald, the Accidental Genius

Bruce Macdonald (b. 1948) is a Vancouver historian and author of the city’s first visual history book. He is also one of the main contributors to our storytelling project and, after he did over 20 interviews with local seniors, we decided it was time to put him on the other end of the recorder.

I’ve never had a main career because I’ve never lasted for more than two years in any job. I was an engineer for two years for Vancouver City Hall. My first desk was actually at the centre of the top floor of the City Hall, which was surprising. I was there for two years, and then I quit and became a schoolteacher, working in three different schools (roughly two years at each school), and in the end, running my own alternative school.

I once applied for a job at the Workers’ Compensation Board and believe it or not, there were just five things they wanted: a person between 30 and 35 years old who was an engineer and also a schoolteacher, and who had a First Aid Certificate and construction experience. I had all that. It was a high-paying job, a really great job, because you ran around and inspected construction sites all day. I liked that kind of work with a lot of variety, out there meeting people. Every day is different. They were hiring 50 people and it took a full year for them to go through the hiring process, so I ended up quitting my teaching job because, for a year, I was thinking I was getting this other job. That was around the time the Workers’ Compensation Board called me in for a physical. So I went and I was in there with a doctor, getting the exam, and I ask: “By the way, do you have any idea why I’ve been called in for a physical?” He says: “It means they’re hiring you.” Then I went home and I didn’t hear from them for weeks, so I phoned up to ask about the current state of the interview. And the guy goes: “Oh, we decided to change our criteria: we want 50 year-olds.” That was the one thing I couldn’t do.

Back in 1980 I ended up joining the Labourers’ Union and worked in construction as a labourer. As a schoolteacher, I was making $2,000 a month, and I will add that my job was pretty good. I had a small school with approximately 10 students and I really enjoyed it. A regular high school teacher had 200 students for the same amount of money, 200 exams to mark, and 400 parents to deal with. It’s a horrendous job; you would never do it if you didn’t get two months off in the summer! In the Labourers’ Union I made $3,000 a month, outdoors getting physically fit. There was lots of variety, doing something different every day. Construction starts out with a piece of vacant land and ends up as a giant building, so every day there’s something in between and there are different people on the job. It’s very interesting. I put a radio with ear pieces inside my hard hat (you couldn’t see it because I had long hair), and I would spend all day listening to the CBC.

I worked that labourer job for five years because I wasn’t married and I didn’t have kids, so I was free to do whatever I wanted. I really enjoyed it. I worked for the Bosa brothers; I actually ended up as John Bosa’s personal assistant. They were eight brothers, all in the construction business. When I worked for them in 1985, they had built almost every three-story apartment building in Burnaby. Now they’re building a huge number of high-rises. At their 1980 Christmas party there were 500 people, and that was when the company was smaller! Unbelievable. I never told John Bosa I was an engineer; as far as he was concerned, I was just a labourer.

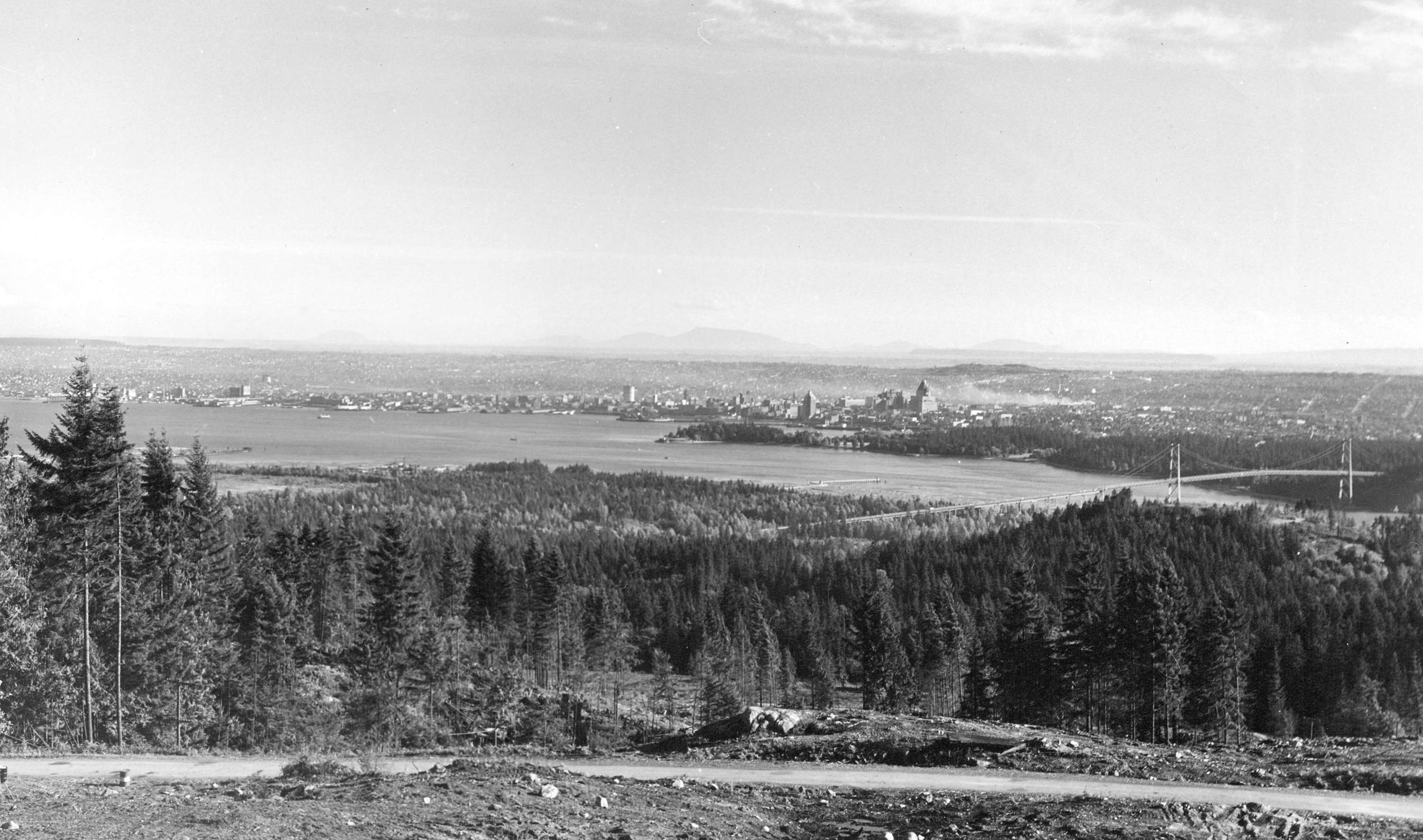

When I was working as a labourer, my mind was free. When you’re an engineer or a schoolteacher, you go home at night and still think of work and deadlines and all you’ve got to do. As a labourer, I was just free to think all day long, and then I would go to the library and look up historical stuff because that’s what I thought about. The thought that really got me was when we were working under the Annacis Bridge building tilt-up warehouses and I realized “Oh my God, I’m at the head of a delta, like at the Nile Delta,” and it made me think “When did people first come here? When did Native people first come here? When did White people first come here?” I had been in school for 17 years in Vancouver and I had never been taught one word about the history of the area. This was a huge hole; I couldn’t believe I didn’t know! We did learn about First Nations people in high school, but all our textbooks were from Ontario, so all the material was on the Huron and the Iroquois, because B.C. is so new that we hadn’t even developed our own textbooks. Before that, our textbooks were from England.

Image credit: Michael Jefferies, CC, Flickr

That’s how I became motivated to find out how Vancouver got started, when First Nations people came here, when White people came here, and I was stunned to find out that people had been living here for 10,000 years. That’s just unbelievable! By the way, I’m the first person (that I’m aware of) who started saying that, because anthropologists and all those guys go conservative and say 7-8,000 B.C., because that’s when they could accurately date items, and they won’t say 10,000 years ago. But that doesn’t mean the item they dated is the oldest evidence, so I would say roughly 10,000 years. And we did learn about Ancient Egypt and things that happened 5,000 years back, and that’s supposed to be a long time ago; then you find out people have been living here for 10,000 years and you start thinking “Wait a second! There’s something wrong with this picture…” So that got me really into pursuing it.

A Mensa meeting unlike any other

When I graduated from Engineering, I had been in school for 17 consecutive years and I didn’t really feel like working. I had a few hundred dollars and no interest in taking a job, so I took the summer off. I lived across the street from City Hall in the attic of an old house with one room, and read books all day, enjoying the summer. After three months I was cutting through City Hall on my way home and I saw a job posting. That’s how I got my job on the top floor of City Hall; it was kind of shocking to stumble onto it. I was there in August, and they had a posting for a summer job. I sort of understood what was going on, that they had four months’ worth of money, and it was going to expire at the end of December, so they were hiring somebody September-October-November-December as a summer student. All the students had gone back to University, so I thought “I should be able to get this job; I don’t have any competition”—this is how lazy I was! I went in there and was interviewed by the Head of the Personnel Department, who said “OK, come back on Monday for some tests—the IQ test, the mathematical aptitude test…” I freaked out because I had taken the summer off smoking dope and reading books and I thought I was going to fail the test.

Image credit: Copyright City of Vancouver

What I ended up doing was going down to Duthie Books (a famous local chain which is gone now, but back then they had 10 bookstores) and found a book on IQ tests in the basement. It was a Banton book, and I needed the Stanford-Binet one, but that was the only one I could find. I went home and did one IQ test (there were five in the book). I got a score of 130, which wasn’t that great. I checked the answers at the back and, at the second IQ test, I got 140. By the time I got to the fifth test, I was at the genius level, over 150, in just a couple of hours!

Image credit: Copyright city of Vancouver

I went in on Monday morning and I flew through the mathematical aptitude test (it was high school level), then I did the IQ test: it was exactly the same test as in my book! So I flew through the IQ test too! I got called in for a second interview and I go, thinking I was going to meet the same guy— the Head of Personnel— but instead there was a table with four guys, and guess who those guys were? Ken Dobell, the rogue scholar who ended up running the city under Gordon Campbell, running the GVRD, and then running the province under Gordon Campbell; one of the smartest people in British Columbia. Then there was the City Engineer, a pretty smart guy; the Head of Personnel; and then the lower boss in the division I was in. All four of them were members of Mensa, and they wanted to meet me, because I had scored one of the highest IQ test scores ever at City Hall! Each one of them asked me one question (probably the hardest questions Mensa had), and each question had about 15 conditions: “What would you do if this, and this, and this, and this…?” By the time they got to the end of each question, I could only remember about two or three of the conditions, so I had to ask them to repeat the questions, but they all said “It’s OK. We understand you’re nervous.” The funny part of the story is that I never get nervous. They hired me, thinking I was a super-genius. So that’s how I got my city job.

Image credit: Copyright City of Vancouver

When they assigned me my desk, it was at the center of the top floor of City Hall. My dad had always talked about having worked at City Hall, so I thought “I wonder where his desk was.” So I ask him at Sunday dinner and he says “I’ve never worked at City Hall.” “What are you talking about? My whole life you told me you did!” And he said “Yes, but I’ve never worked at that City Hall; that was built in 1936. I worked at the City Hall that next to the Carnegie Library, at Main and Hastings, but they tore that one down in 1928.” All this kind of stuff got me interested in history.

Image credit: M. James Skitt Matthews, public domain

My dad was a civil and geological engineer. I’ve always been interested in real estate, but my dad never believed in buying property. He didn’t think real estate value would go up in Vancouver, because he had seen property prices go down before the 1960s. Because he had been a wing commander in the War, he qualified for a low-cost loan from the Government. When he got enough money together from his job as an engineer at BC Hydro, he decided to build his own house. The condition to qualify for the loan was to have 1.6 acres of land. We used to go for drives every Sunday and then go to Peter’s Ice Cream after that (that was kind of a Vancouver tradition). So we started driving around looking for a 1.6-acre lot, but there was no lot in Vancouver that big. The biggest lot he could find was 1.1 acres in West Vancouver, so my uncle bought the lot next to it and sold it my dad. It became the biggest lot in British Properties.

The current owner is the same guy who got into trouble last year for fixing up the old hotels in the Downtown Eastside and evicting the poor people, so they protested him in front of his house—the very house where I grew up. This guy is so rich that not only did he buy my parents’ 1.6-acre lot, he bought the lot next door, so now he has a 2.5-acre lot in British Properties. He tore down our house last year. It was a brick house; I couldn’t believe it, I didn’t think that would happen. Now he’s building an 11,000 square foot, five million dollar house with a 100 foot swimming pool. This is how things change. My father bought a 1.6-acre lot in West Vancouver for $4,000; 1 acre on the West Van waterfront now sells for 42 million dollars.

Image credit: M. James Skitt Matthews, public domain

Child prodigy by elimination

In high school, I got really good grades by studying all the time, but before Grade Six I hadn’t really studied. I was a C-student, just an ordinary kid having fun. Then we moved to Abbotsford in 1959 when I was in Grade Four, and then in Grade Six, at Christmas, exactly halfway through the school year, we moved back to West Vancouver. At the school in West Vancouver, the teacher asked us questions like “What’s the capital of North Dakota?” Everybody just sat there, and I said “Bismarck!” because I had just learned it a week before at the school in Abbotsford—it was the same material, just in different semesters—so I knew EVERY answer, and nobody in the class could believe how smart I was! All of a sudden, I was this genius kid, and it started to feel good, so I started to take tests seriously and I got really good at preparing for tests. You know how the teacher says “You better learn this because it’s going to be in your Christmas exam!”—I would write that in my notebook while everybody else would be sitting there looking at the window and I would get close to 100% on my tests.

Here is the other part of the story: in Grade Eight, we had a PE teacher for homeroom and early on in the school year he came in at 9am and handed out some tests to the whole class and said we had an hour to complete them. He sat there for about a minute and then he got up and walked out of the room. I thought “That’s interesting; he left. He’s a PE teacher, a slacker, doesn’t want anything to do with work.” After about 15 minutes of doing this test (it was really hard), I get out of my chair and I realize he’s not coming back, so I started walking around, punching my friend, talking to my other friend. For about half an hour, I milled around the classroom, and then I only got halfway through the test before the time was up. It turns out it was an IQ test, and I basically failed it. They had come up with this new program where they skimmed off the really intelligent kids so they could do four years in three, and I wasn’t asked to join that program because my IQ was too low. And because I was studying all the time and the most intelligent kids had been taken into the program, I always got the highest marks in every subject! Teachers weren’t happy; they thought it wasn’t fair that I got all the awards at every ceremony, so they wanted to give me only one award and spread the others among the rest of the kids. Anyway, that’s how I accidentally became a top student.

The book

After working as a labourer for five years, I got the idea of writing a book about Vancouver. Before that, there were only two books about Vancouver (From Milltown to Metropolis by Alan Morley and Vancouver by Eric Nicol). Both authors were columnists, so they had the material to put into the books because they’d already been paid to write the columns. They were really interesting works, but they didn’t have pictures or maps. That was frustrating because we live in such a visual world, and I thought that what we needed were lots of illustrations. I came up with what I considered to be the ideal layout, really a companion to any book on Vancouver, but it also works as a history by itself. I used to go to my labouring job and then work on it at night. In 1984 I finished what I call my mockup and I used film to do the colour part, which was hard to do because I had to cut it out with a razor blade and stick it on. Then I bought a computer to print out text. I ended up with this really beautiful and colourful mockup; it looked fantastic. Then someone told me: “You know, they have a whole pile of money for the Expo ’86. You should apply for it.” So I applied for it and the guy, the big shot in Downtown, calls me and says: “I have good news and bad news for you. We’re funding 200 projects with this money. You have the best project, but we just gave all the money away last week.”

That’s what they do whenever there is a big commemorative event: they give out millions of dollars. For the sesquicentennial of the Gold Rush in 2008 the province gave Vancouver 10 million dollars to celebrate. And you know what happened to that money? That’s how we got the neon signs, like the Rainier Hotel neon sign, or the Pennsylvania Hotel sign. So there is money out there, and how do they spend it? But I didn’t really want to do the book, because I knew that it was like 10,000 hours of work, which was way too much. A year later, somebody told me that the Head of the History Department for SFU was coming to their next meeting and that I should show him my book idea. So I dug up my mockup and I went up to the guy and said: “I have this idea for a book. It’s a decade-based book on Vancouver with a map in the middle, with 10 great people from each decade, with graphs to cover the economics, etc.” He looks at the mockup and says “This is a great idea. You should apply for an SSHRC (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council) grant.” I’d just finished being a labourer and I was working for Statistics Canada at that time, on the census.

I looked at the grant application, and it was a big research grant for people doing their Masters and PhD’s so that they could spend a couple of years extracting information from some archive somewhere and then write a thesis on it. I hadn’t even taken one History course before. So I told him: “I don’t qualify for this ten different ways” but he said “No! I think you’ll get the grant.” He could tell that I loved the topic and I had all the passion and the drive, and he knew I would do it. So I got a $100,000 grant and I delivered the book right on the deadline.

I wrote my book with immigrants, children, seniors and non-English-speaking people in mind. I knew they would get something out of it because it was so visual. A lot of history is invisible, and part of the reason I get bound up in doing all these little historical projects is a lot like being Sherlock Holmes: a history scene is much like a murder scene. You go there, and there might not even be a body anymore. All you can do is look around for clues, and if you get the tiniest clue it can become really important. If you get a whole bunch of all these seemingly-irrelevant details and bring them together, you can solve the crime. That’s what doing history is like.

Leave a Reply