Ivan Sayers: “History Is My Thing; Fashion Is Just the Medium”

Ivan Sayers (b. 1946) is a well-known fashion historian and owns one of the largest historical clothing collections in Canada. His latest production, From Rationing to Ravishing: The Transformation of Women’s Clothing in the 1940s and 1950s, was a tremendous success and a perfect fit for our story project.

Image credit: Tania Goehring, Creative Commons

Ana-Maria Gheorghiu: You arrived here in the ’60s from a small town, Summerland, BC. Did you already know you wanted to work in fashion?

Ivan Sayers: No, I had hoped to become an archeologist. My approach to clothing is from a historic perspective, always. Some of it is very beautiful, of course, but I always tell people that history is my thing and fashion is just the medium.

If I had become an archeologist, I would have had to get a doctorate, I would have had to teach for the rest of my life, and I do like teaching, but, in the kind of work I do, I don’t have any serious competition. I’m essentially the only person who does what I do here. I know one or two people who sort of do what I do, but everybody does it in their own way, and those people don’t work here. There’s a fellow in Ontario who’s from here and sort of does the same thing I do, and I know there are people in the States.

A. M. G.: I was watching the other day one of those clips from the late ’50s that was talking about the fashion of the future, with designers imagining the fashion of the year 2000, and I wouldn’t say that, overall, they were that far off. Of course, there were also some far-fetched theories predicting that the skirt would disappear altogether or that there would be self-cleaning clothes. Did you give that any thought back then, to how people would dress in the future?

Ivan Sayers: I was just talking to someone and I said I had a book that has an illustration from the 1890s predicting what women would be wearing in the year 2000: trousers and boots. And that’s essentially true. The only difference is that they predicted that women would be smoking, they show the women with a cigarette in her hand. Now there are certain women who smoke, and nobody thinks it’s inappropriate to have a woman smoking but they think it’s inappropriate to smoke, regardless of gender. As for the skirt… you’re wearing pants; all the women around us are wearing pants…

When I was in University, I had friends who did avant-garde design, and they would tell me what they thought about the future of fashion. But I was always more interested in the past than in the future. Of course, it’s a game you can play with yourself, but it’s a dangerous game, because you’re never right. For example, I would have never predicted that women would be covered with tattoos. Women who wore tattoos worked in the circus, or were prostitutes, they were on the lowest levels of society. Even for men… My father, when he wanted to get my mother angry, would tell her that he was getting a tattoo. I personally think they’re terrible, mainly because they are permanent and fashion changes all the time, but I’m old and I’m biased, so there you go. Now they are worn by very respectable women and very respectable men, and it doesn’t have the same meaning anymore. I like some of the artwork, but I still think it should be on a wall, or washable.

A. M. G.: As we know, East Vancouver has always been a working-class neighbourhood. I have asked some of the ladies we’ve interviewed for this project what they aspired to in terms of clothing, and the answer was almost invariably: a cashmere sweater and a tailored skirt. It seems so humble compared to how we consume today, yet people used to look a lot more polished than they do now.

Ivan Sayers: Generally speaking, whenever the economy is poor, it’s important to look successful, because, if you’re failing, your pride goes. But as long as you’re still working and you are productive, you are the “respectable poor.” Both my parents always worked, they went to church, they paid the rent (because they rented; they didn’t own the house), they were still neat and clean, drove a car, went to work on time, had pay cheques and paid taxes and so on, so they were the respectable, working poor. And we still have a lot of that now in Vancouver because, if you’re a young couple, even without children, how do you buy a house? A lot of them have given up on home ownership, they don’t even think about it.

It is psychologically important to look and feel like you’re looking after yourself. You want to have a job, you want to pay your bills, so you want to look clean and smartly-dressed, you want to look current and fashionable without looking trendy. Many years ago, I spoke to an elderly European woman who came here in the ’30s, and they had tremendous amounts of money back in Austria, they were extremely wealthy in those days, and she said: “You should really be speaking to my sister-in-law; she’s the one who had the real money and the real social life.” And I said: “Oh, was she stylish?” The woman thought about it for a moment and said: “No, she wasn’t stylish; she was elegant.” Big difference. Especially to her—she’s 96 now. In her youth, if you were stylish, it meant you were trendy, but if you were elegant, you bought classic things that always looked beautiful. I was buying clothes from her and, sure enough, that was the kind of things she had.

A. M. G.: So there was no emphasis on having fun with fashion like it is today?

Ivan Sayers: No, and now fashion is also seen much more as art; it’s supposed to be an expression of your personality and your individuality, and you’re not supposed to look like everyone else. Novelty is important, and abundance. You go to a thrift store and there are literally hundreds and hundreds of items in that room that are not worn at all, or worn just once or twice. I don’t care, you know… I’d rather save the money and do something else with it. That’s why I don’t have things now, because I’ve always live like I was poor, even though I had a job.

A. M. G.: You might even find something better quality at the thrift store than you couldn’t afford to buy retail.

Ivan Sayers: Absolutely! Designer things, like Issey Miyake, things you might not necessarily think to buy, but then you look at the label and go “Oh! This coat probably sold for $400 and it’s $29.99!” But I always, always tell people, even collectors: only buy because you like it. That’s the most important thing of all. If you don’t like it, you’re not going to wear it, so it’s not a bargain.

Image credit: Jack Lindsay, public domain

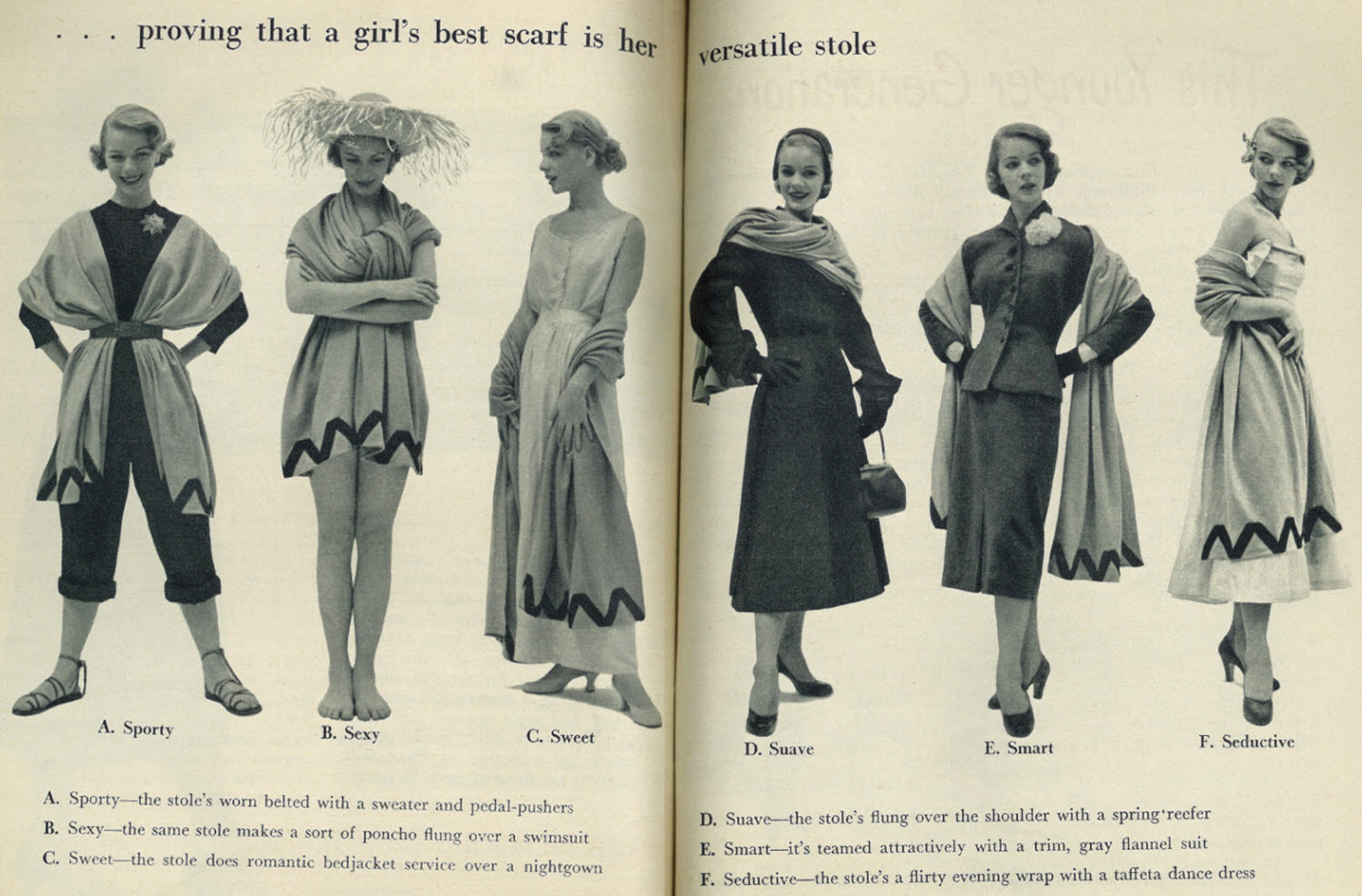

A. M. G.: What were the must-have’s in the wardrobe of a woman of the 1950s?

Ivan Sayers: We were talking about women wearing suits. In my childhood, my mother worked in an office. Her boss was the Inspector for the Department of Agriculture for the Okanagan Valley, and my mother was his secretary for many years when I was very young. In 1956, when I was ten, my mother always had to have a grey flannel suit, and she always had to wear plain serviceable high-heel shoes, sensible ones. Everything had to match. In the summers he would have at least one pair of white shoes, and, in the winter, black or brown or both. Those were the basics. Then she would have one pair of dressy shoes, usually sandals, black, with heels, for a cocktail party or a New Year’s Eve or whatever. Also, she always had to have at least two cotton summer dresses that she could wash in the washing machine. And then she would have a good dress that she could wear to a wedding or dinner at someone’s home. Her wardrobe wasn’t large, but it was smart and decent quality, because my mother sewed, so she made a lot of her own dresses. She always bought her suits though, because they required too much work. My father was pretty much the same—he always had a tuxedo, because he also played in bands, he was a musician. He was a labouring man for the most part in those days; he worked for the railroad, he worked for the highway, but because he sometimes worked in a band, he always had a tuxedo.

Image credit: Classic Film, CC, Flickr

My mother, very rarely would she have had an evening dress long to the ground, because they just didn’t have that kind of lifestyle in the country, but she did have a cocktail dress for semi-formal situations. A basic wardrobe. Always wore stockings, always had a hat, or a variety of hats. She would always have a winter coat and a summer jacket, and always had a pair of trousers for hiking but also a pair of trousers for car trips. My parents rode horses, but I don’t remember my mother ever wearing blue jeans, even when she went horseback riding at my aunt’s ranch. My father wore blue jeans to to work. Denim was for working in the garden or picking fruit in the Okanagan.

Image credit: Allison Marchant, CC, Flickr

I think one of the reasons that I examined clothing as an artifact of social history is that my mother and all of her sisters, and my father and his friends, were always very very conscious of their appearance. And I still feel that clothing is the most personal artifact that you can possibly examine, because you wear clothing that you think complements you but also illustrates the kind of person you are. So you wear something that lets other people know your character, and it also helps you connect with other people of like mind. If you’re young, you often wear extravagant clothing, because you want to be noticed. Even punk clothing, it came from big cities and it was popular first amongst young people whom no one was going to pay any attention to, so they wore theatrical clothing. Being ignored is very difficult for young people. Now that I’m getting older, I wear more and more nondescript, bland clothing because I don’t want to be noticed. I’m not trying to pretend to be modest or anything, because I’m proud of my work, but, at the end of the day, I’m busy, I’m in a hurry, I’m tired, and I get enough public reactions from my programs and whatnot. It’s too much work! That’s what I do all the time: I’m dressing mannequins and I’m dressing my models. People always ask me what I’m going to wear on Halloween and think it must be my most important holiday, but on Halloween I stay home and watch what other people have done. I don’t dress anybody up, and I don’t lend things to people.

Most people who are collecting vintage clothing collect it for their wardrobe. They want to wear it because it implies a certain kind of personality or lifestyle to them. Women who dress ’50s style do it because they want to be seen as Marilyn Monroe or Elizabeth Taylor or Lucille Ball. There’s an exaggeration of the feminine, and they want that femininity back but they don’t want the politics, and now they can have it both ways. I was talking to a woman the other day: total ’50s looks, but covered with tattoos.

Image credit: annapolis_rose, CC, Flickr

A. M. G.: I think the revival of the ’50s is largely because of Mad Men, but it’s more of a caricature of the 50s that borders on fetishism.

Ivan Sayers: Absolutely, that was a major contributor. Revivals always are caricatures and there is a lot of fetishism in them. Marilyn Monroe is more famous now than she was in her own lifetime. You see even the vaguest interpretation of it and you know right away that it’s meant to imply Marilyn Monroe, a blonde woman in a sexy dress. It is a costume, and it’s fine, it’s all fine, but you cannot go back, and, even if you could, you wouldn’t want to. I say frequently, especially in a class or to an audience, that the lesson of history is that you are better off now!

But that can change. That’s why I was yelling at the audience: make sure you vote and vote responsibly, because that can change, and sometimes the change gradual, especially when they can focus fear and paranoia towards a certain group.

A. M. G: Was there any noticeable influence in fashion from the waves of Italian immigrants who came to Vancouver?

Ivan Sayers: Certainly, in Vancouver, the Italian community gravitated to Commercial Drive. You went there if you wanted pasta, before pasta and pizza was everywhere. And there were Italian tailors on the strip then, who competed with Chinese tailors and Jewish tailors. So you went there if you wanted Italian tailoring, because maybe the pants were a bit tighter or different in some way. There was a famous Italian shoe store on The Drive; it’s still there, and it’s still famous.

A. M. G.: What were the markers of quality for people who weren’t label-savvy? Did it matter where clothes came from?

Ivan Sayers: When I was a kid in high school, in the Okanagan—I’m from a very small town with 1,200–1,500 people—if girls wanted a new dress for a high school dance, they would go to Penticton which is 12-13 miles away; bigger town, more selection. If you bought your dress there, no one in Summerland would know what you paid for it. So the girls in Summerland would go to Penticton; the girls in Penticton would go to Vancouver; the girls in Vancouver would go to Seattle; the girls in Seattle would go to San Francisco, and the girls in San Francisco would go to Los Angeles. That’s the chain! They always wanted to go to a slightly bigger, more sophisticated city, because they wanted to look sophisticated, they wanted to look like the women in the bigger cities. It still goes on.

American taste has generally been brighter than Canadian taste. Canadians like to be safer, but Americans like to take chances and be noticed. We are traditionally known for being very polite, and part of being polite is not being pushy, so you dress down. It doesn’t mean anything significant, and there’s also a practical aspect to it. Elderly Italian women used to wear all-black; now that’s not the case any longer. In the old days, when you were widowed, you wore black, which meant “stay away from me; I’m not interested” (unless you were young and wanted a new husband), but it was also practical because, if you buy nothing but black clothing, everything matches and it doesn’t date; you can wear the same black coat for six years and no one will notice the difference. Whereas if you buy a pink fluorescent coat that’s on the rack at Le Château, by next spring everyone goes: “Oh, she’s still wearing that coat!” It’s all part of the game and it’s not serious, but fashion isn’t terribly serious unless you’re in the business and trying to make millions.

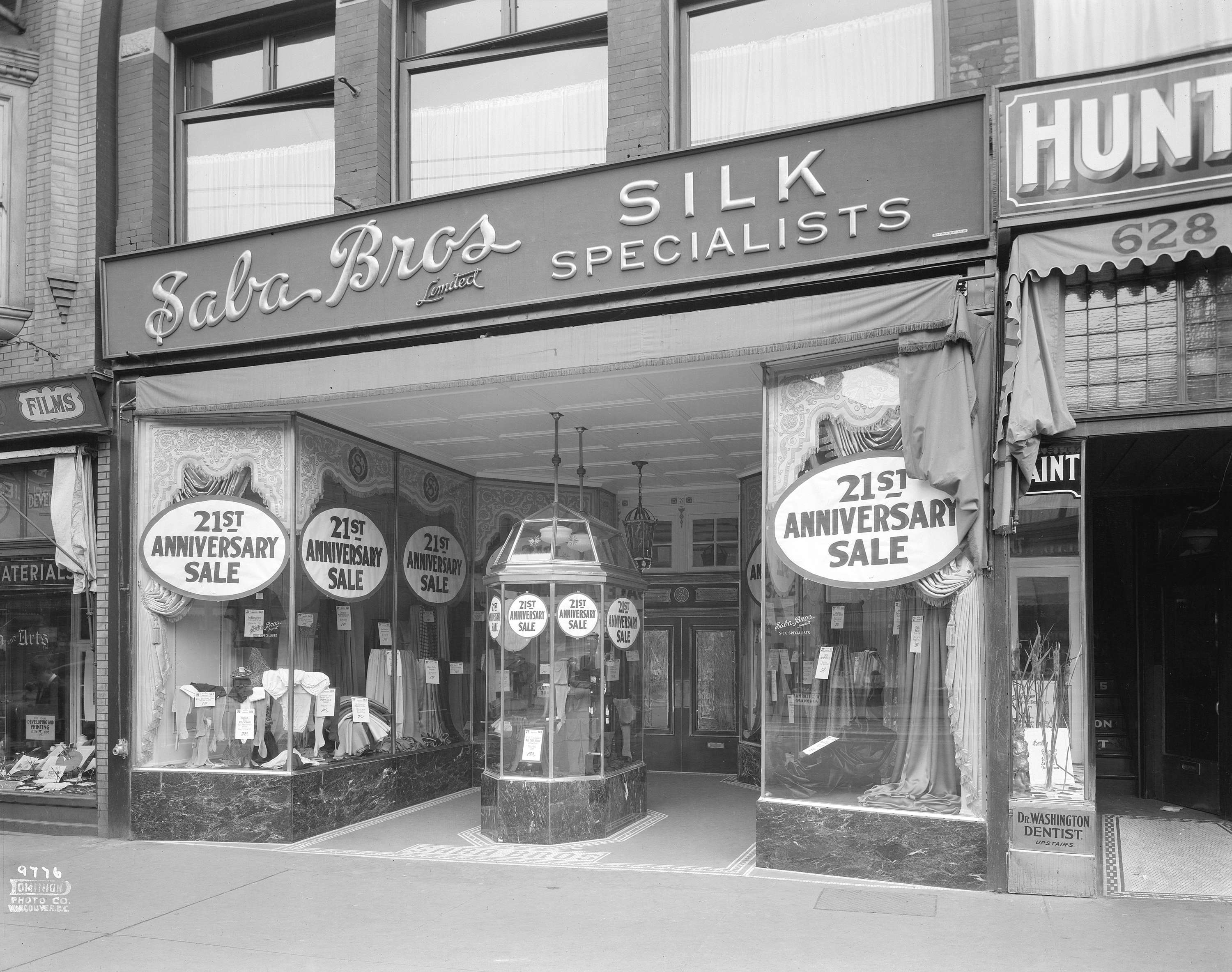

A. M. G.: Speaking of business, when I was going through the Vancouver archives, I saw a fabric store that seemed to be popular called Saba Bros. Silk Specialists. What can you tell me about the clothing and textile businesses of those times?

Ivan Sayers: Saba’s was very popular; they were originally (I think) from Lebanon. They were two brothers who started that business with a push cart. They went through the neighbourhoods of the city, to Dunbar and Kerrisdale, with a push cart with pulled ends of fabric from factories and cups and saucers. They walked up and down the street selling fabrics and teacups. They would buy the fabric from the factories at nominal price and then sell it off a little bit at a time. Immigrant experience: they worked hard, saved their money, gradually got a storefront, gradually got to buy the building the store was in. Saba’s was on Granville Street over here, and it was the most important place to buy fabrics. For a long time they didn’t have any serious competition. They sold ready-to-wear clothing as well, very expensive and very good.

And that’s what immigrants learned: they knew that the profit was selling quality. Always sell the best thing you can afford and charge accordingly. Don’t sell fabulous things for cut-rate prices; sell fabulous things for fabulous prices, and then you make your fortune! That way you can look after your children and send them to university, because a lot of immigrant people couldn’t go to school. My father’s grandfather came from Ireland in the 1870s, and his immigration papers were signed with X’s because he didn’t know how to read and write even his own name. In the 19th century, the English wouldn’t let Irish children go to school and learn how to read, because if they learned how to read they could organize and create a rebellion.

Everyone wants basic things, regardless of what culture they are from: they want a roof over their head, food on the table and to be able to look after their children safely and give them a decent future. And the immigrant population is massive, and they all want to do well, so they try harder.

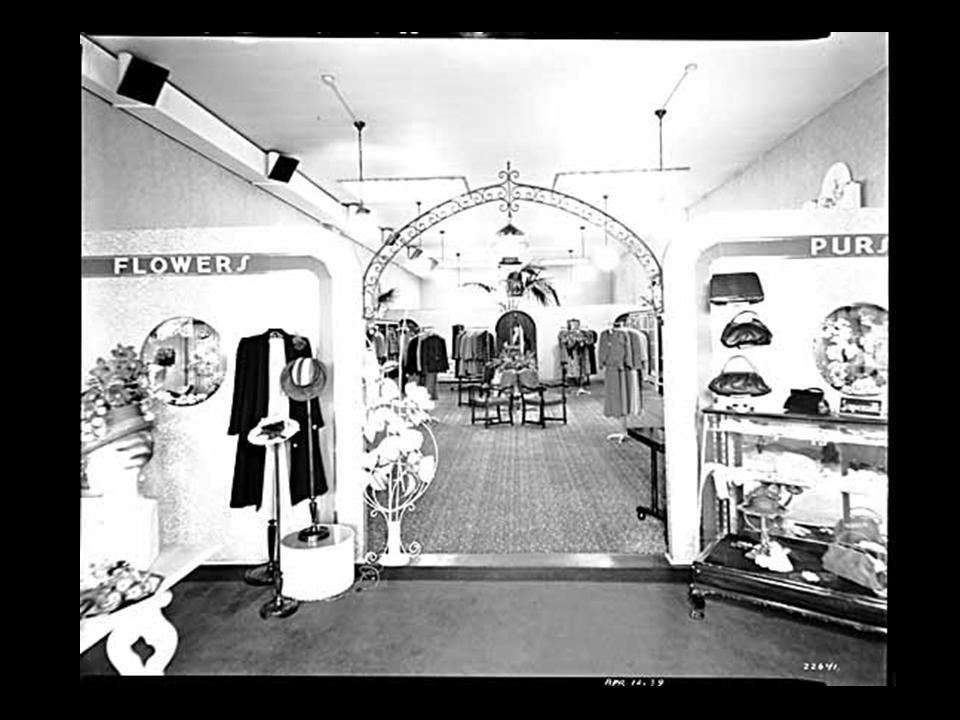

Then there was Gold’s, a Jewish merchant, again, the same thing: they had a business on Granville at 8th, a big store.

Image credit: Townley, Matheson and Partners, public domain

A. M. G.: For our generation, whether we make more or less money, shopping is seen as a pleasure you should offer yourself regularly, maybe two-three times a month, but I know that wasn’t the case before, especially after the War. How often would a woman go shopping back then?

Ivan Sayers: You would buy something new when you needed it. It wasn’t frivolous. It was essential, and it was one of the reasons many women would have sewn their own clothes. Also because it was seen as a woman’s responsibility to know how to sew. Boys knew about mechanics, girls knew about other things. The only thing girls knew about mechanics was how to use a sewing machine, but not how to fix it or maintain it.

Image credit: Donn B. A. Williams, public domain

A. M. G.: What was the relationship between politics and fashion, since we are talking about the 1940s?

Ivan Sayers: My expertise is in historical clothing from the 1700s and up, so I can’t give you specific examples of politics in fashion before that. But certainly there are many, many examples of people who would have worn a specific colour to show allegiance to a certain political party, or emblems that you would wear to show association with one royal house or the other. There’s a whole premise on examples throughout history of women wearing clothing that is actually borrowed from your enemy. During World War II… You know what a dirndl is? A dirndl is a German folk skirt. The Tyrolean costume as they wear in the Alps is a dirndl skirt, a little vest and a puffy blouse. A dirndl is a plain strip of fabric gathered evenly around a waistband. They were hugely popular in Canada and the United States during World War II.

During the Napoleonic Wars, it was very very popular in England to wear white kid leather slippers with bumblebees, the Napoleonic emblem, painted on them. I’ll give you one more example and then I’ll tell you why we think that is the case. Right now, how many men are wearing beards? And who’s portrayed as the common enemy? The Muslims.

A. M. G.: I would have thought this is more a reaction to feminism than anything else.

Ivan Sayers: Oh yes, there is that too! Being super-manly, especially for very young men. But, through the propaganda in the news, by the American government in particular, they portray Eastern Mediterraneans and Muslims as a potential enemy. But the men here are looking like them more and more, because the psychology is, if you take elements from the everyday wardrobe of your enemy, you are making the point that the enemy is not the people—they are just like you, and you are just like them—but their government, and you’re going to invade their country because you’re going to liberate them from an oppressive regime, you’re going to save them.

A. M. G.: As a way to soothe the conscience?

Ivan Sayers: Exactly. As I said, this theory, it’s just theory, but it’s a very interesting thing to discuss because it appears over and over and over again throughout history. In Germany, during World War II, it was very popular to wear tartan, stewart tartan. I hope it’s not the case, because I don’t want to see another major war, even if people think they’re rescuing their enemies from an oppressive government, because usually wars are fought all about money and power.

Image credit: Jessica Hartman Jaeger, CC, Flickr

A. M. G.: I was also curious about the money in the industry and how that changed direction because of the War.

Ivan Sayers: Certainly, in terms of North-American economy, the war meant you couldn’t get supplies from Europe or from Asia, so the American garment industry flourished, especially in New York, with local designers and manufacturers. There were other consequences that you don’t think of. For example, across the street here (W Hastings St.), a hat factory opened up right at the beginning of the war because they couldn’t get hats from Europe, or artificial flowers from Germany and Czechoslovakia, or straw hat forms from Asia. So the local hat business flourished. There was a woman a couple of blocks over here who couldn’t find party decorations, because all the party decorations were from Germany, so she started her own factory in her building, making crepe paper flowers and streamers and things like that. Her business flourished because of the war.

Image credit: Stuart Thomson, public domain

In Europe, the bombings slowed everything down, so consumers had to stop, but the void in the garment industry was taken up by the military, because suddenly the government needed thousand of uniforms, parachutes, blankets, bandages, so those factories went from making pretty dresses to making uniforms or socks for the soldiers, or boots instead of high-heel shoes. The economy still functioned, but the way it functioned changed. Some people lost everything, other people made fortunes. Wars are big business. At the end of the War, the only country that came out financially solvent was the United States.

A. M. G.: It’s rather hard for me to imagine what war meant in a country that didn’t have war on its own land. It’s such a different experience.

Ivan Sayers: Absolutely! If you’re looking for vintage clothing anywhere in the world where you want really good high-fashion items, you go to the United States, because they never had a war on their own land. They were always rich, and there was a large population who could afford to store things because they had houses with extra rooms. In Germany, they told everyone to clean out their attics and burn everything because, if the attic was full of old clothes or paper and there was an incendiary bomb it would promote the fire. In Dresden and all of those major cities, it was the actual fire, not the bombing, that destroyed everything. I have American friends who talk about how tough it was in the U.S. during the war and so on, but they really have no idea. I don’t have that experience either. I was born right after the War and I’ve never been in a building that’s being bombed, in the dark underground, waiting for the hot water pipes to burst so, if the bomb doesn’t get you, the hot water will kill you. And wondering how long it will take, and how much fear you have when you’re in there with your children. It’s terrible… no wonder people came out permanently damaged.

I knew two sisters who had been born and raised in Shanghai (they were of Portuguese extraction and their family had been there for several generations), and they had been in a concentration camp in Shanghai. The only thing they were able to save was their knitting books. They lived together in North Vancouver, they never married, and, when one of them died, I was invited to go and see if there was any clothing there I wanted. They cleaned out the main floor of the house, but the basement was where they stored their clothes. There were 40 black coats, all exactly the same, more or less. The whole basement was covered in old chests, actually big fruit bins, filled with clothes; all rafters had pipes on them, all with hanging clothes. There were thousands of pieces of clothing in that basement—not one of them any good. They had gone to thrift stores, they had gone to garage sales, and they had bought, and they had bought, and they had bought, because they had lost everything and they were never going to let that happen again. It was a mental thing, that was the scar.

My colleague, Claus, buys things online for his collection from the former Eastern Block countries, and he periodically finds shoes that were made in Germany during the War that have been hoarded and have never been worn, 60 years later. Those shoes were so precious to the person who got them that they were hid and kept because tomorrow might be worse. So wear the shoes you’ve got today with the holes in them, because tomorrow they might not be good anymore. And dresses as well… You can understand why people get like that when they lost everything.

A. M. G.: That’s one factor, and this is also a class marker, because poor people tend to save clothes for that special occasion that never comes. My grandmother has a closet full of new clothes but wear the same ones every day.

Ivan Sayers: Exactly, who are you saving it for? With my collecting too… In the world of museums, I’m not a responsible man, because the stuff is seen as sacred and is supposed to go into storage and it sits there for ever! Now I do what I want, because I’m old and I have my own collection, but I still tell them: who are you saving it for? Which generation is worthy? This one, this generation is worthy, every generation is worthy! So you save it until you save enough of them, and you look after it and use it responsibly so it doesn’t wear out. If it’s 400 years old, of course you save it and you handle it with kid gloves and only use it in the most appropriate situations, but, if it’s 50 years old and you have 200 of them, they must earn their keep! Everything must earn its keep, regardless of what it is. we have to! If you’re not productive somehow, then get out of the way! The guy who started McDonald’s said: “Lead, or follow, or get out of the way!”

A. M. G.: Vancouver was recently voted in GQ Magazine as one of the worst-dressed cities in the world. What do you think about that?

Ivan Sayers: That wouldn’t surprise me. The West Coast lifestyle is notorious; everybody is seen as very casual to the point of being sloppy. There’s an argument for that, but I think it’s mainly because people are busy. It also has its roots in the hippie culture of the late ’60s-early ’70s when Vancouver really started to blossom and grow, hugely. Because of the hippie attitude, if you dressed up, it was pretentious, and people didn’t want to be seen as pretentious. Now it’s a bit different because there’s so much money here, and there’s a large immigrant population who want to be important and contribute and be equal, and one of the ways to be equal is to dress up and prove that you’re doing well. So they want to go to Holt’s and spend $2,000 on a blouse.

A. M. G.: Would you say that, 50 years ago, a tourist from Europe would have said the same about Vancouver?

Ivan Sayers: Absolutely. You have to keep in mind that Vancouver is not an old city, and up until 50 years ago it was still conspicuously a mill town. The logs were shipped out of Vancouver. When I was a boy, there were still sawmills in False Creek, and now False Creek is very trendy. All the forestry around here, even in Stanley Park is second growth or third growth, because the original forest was logged off at least once.

Image credit: James Crookall, public domain

Image credit: colink., CC, Flickr

Now, go down Main Street: there’s hundreds of little boutiques by all these graduates from design schools trying to make it big, and some of them might. A lot of them have skill and talent, and it doesn’t matter where you are; if you’re talented and work hard you can be important. In a big fashion city, you’re lost. Patricia Fieldwalker—she sells in New york and London now; Zonda Nellis started off here hand-weaving and now she sells in New York and L.A., all over the place; my friend Melanie Talkington makes corsets (she went to school in Richmond, at Kwantlen) and she’s now selling in South America, in Paris, in New York… She’s not rich yet, but she’s going to be!

A. M. G.: What were the most popular local labels of the 1950s?

Ivan Sayers: Here, for the most part, there were two or three well-known local dressmaker designers, Mrs. Wiener, Lore Maria Wiener, was probably the most important and the most expensive. I know her quite well; she’s still alive and she’s 94. She came here through the vagaries of the War, left Germany in 1940 and went to Shanghai because they didn’t need to have a passport, then, after the communist takeover of Shanghai in ’49, they came here, Because she had been trained in Vienna in the 1930s, her techniques were spectacular: she knew how to put a zipper in properly, she knew how to finish a pocket, all of these things. She had a European training that women here didn’t even think about. So there were two or three people like that. Madame Runge—the original Mme Runge was a French woman but she didn’t do custom-made stuff; she would buy ready-to-wear French imports. Eaton’s and The Bay would get French imports through brokers in Paris, they’d get samples.

Image credit: City of Vancouver, CC, Flickr

I have in my exhibition a blue silk dress from Pierre Cardin that still has the price tag—it was $350 in 1959. My first rent, when I came to Vancouver in 1965, in a rooming house in Kitsilano (2nd floor, one room, a hot plate and shared bathroom): $8 a week. The woman I got the dress from lived in West Vancouver, and I believe she was on the Board of the Vancouver Symphony or the Opera. I don’t know what her husband did for a living, but they were well-fixed, they had money. She bought it on sale though, it was marked down to $250.

Image credit: Donn B. A. Williams, public domain

There were also brands from Montreal and Toronto that made good quality clothing, and Scottish sweater stores like Dalkeith, which was a major brand. You had to have a Dalkeith pullover and a matching cardigan. I have hundreds of mail-order catalogues and magazines at home, and that’s a good way to find out what the popular brands were.

Image credit: Copyright City of Vancouver

A. M. G.: At your latest exhibition, you were talking about Lauren Bacall. The world knows all about the American fashion icons of those times, but nothing about the Canadian ones. Who were the trendsetters in Canada?

Ivan Sayers: There were Canadian magazines like Chatelaine or Mayfair (which was meant to be Canada’s answer to Vogue in the 1940s), the Canadian Home Journal, more modest publications for the farm women in the Prairies, or the Star Weekly which had a magazine insert that would often have a fashion insert or fashion feature. Then there were the editors of fashion magazines who would talk about a certain Montreal designer or about the latest fashion from New York available at The Bay or something like that.

Image credit: Allison Marchant, CC, Flickr

Image credit: Jeff Shimoda, CC, Flickr

In Canada, the unifying feature was CBC, so there were women who appeared regularly on television and helped promote a sense of modern fashion. There was a singer named Juliette who was on Saturday nights on CBC, right after the hockey game, so she was hugely popular. There was a woman named Gisele Mackenzie who played the violin and was very glamorous. There was a game show called What’s My Line? and there were women on the panel there who were quite fashionable. And the French-Canadian women! When I was thirteen, we lived in Northern Ontario for a while and we rented an apartment from a French-Canadian family. Madame Arsenault was the most fashionable woman I had ever seen. She’d had eight kids already, up in the middle of nowhere, and, man, when she got put together—she wore a corset, I know she did, because she couldn’t have had that figure after eight kids—was she glamorous! And the rhinestones, and the hair… It doesn’t matter where you are, you still want to look good.

Image credit: Classic Film, CC, Flickr

I don’t know if you’ve ever been to Whitehorse. There’s an art gallery there, and the art is spec-ta-cu-lar! So you never know… Some of the most fabulous clothes I’ve ever found have come from the most peculiar places. There was a family named Cantoni that lived in Vernon. They were Italian aristocracy and, in the 1920s, they left Italy for personal reasons. The mother and daughter moved into this nice but very modest house in Vernon, and, once a year, they went to Europe to buy clothes, primarily in Paris. When the mother died, the daughter was by then in her ’60s or ’70s and she didn’t have any money, so she decided to sell these clothes they had bought in Paris in the 1920s and ’30s. So somehow, because she was smart enough, she got hold of an auction house in New York and got $91,000 for them! And that was 30 years ago. A friend of mine bought most of them and sold them to the big fancy Costume Museum in Kyoto, in Japan. The dresses by Madeleine Vionnet that she had are considered to be some of the best examples of her work in existence! And I know that he got at least $10,000 a piece for those dresses… and that was in Vernon. And they wore them there in the 1920s and into the ’30s. My friend Claus has a hat that belonged to Carmen Sylva, the Queen of Romania, a remarkable woman.

Image credit: 晓波 傅, CC, Flickr

Image credit: Sacheverelle, CC, Flickr

Leave a Reply